by Angela Doll Carson

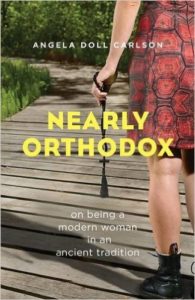

Next in our series on women coming into the Orthodox faith without their husbands, this article is actually an excerpt from Chapter 9 of Angela’s book, Nearly Orthodox, which you can purchase from Ancient Faith Publishing, and from Amazon. Our thanks to Angela for allowing us to republish it. Buy her book as a way of saying thanks!

Next in our series on women coming into the Orthodox faith without their husbands, this article is actually an excerpt from Chapter 9 of Angela’s book, Nearly Orthodox, which you can purchase from Ancient Faith Publishing, and from Amazon. Our thanks to Angela for allowing us to republish it. Buy her book as a way of saying thanks!

Follow: On Going It Alone

The beginning of love is the will to let those we love be perfectly themselves, the resolution not to twist them to fit our own image.

—Thomas Merton

The hardest part of the journey, harder than the struggles with prayer and fasting, harder than figuring out how to parent my crazy brood of chaos-makers during Liturgy, has been knowing that I was going first into this ancient tradition and that maybe my husband would never choose to become Orthodox at all. On some level I knew it was all right. My priest told me it was all right. I understood my relationship with God begins first in me; it has to begin in me. For as long as I seek to have my faith dependent on another person, it will always be shifting as that person shifts. No matter how strong and dependable he is (and he is strong and dependable), my husband will always be human, always changeable. Following God into Orthodoxy meant I was going it alone.

The whole idea of the man as spiritual head of household had been brought up to me throughout the course of my conversion, albeit with a sideways sort of approach. It usually fell to about the third thing people would say about my decision to convert, after “Is it Jewish?” and “I’ve never heard of that.” It’s always a question, but I hear it as a judgment. I think I hear it as a judgment because I am, myself, judging. Moving into Orthodoxy was already a struggle, but to go it alone made it more awkward, the road more rock-filled, and no matter how often I heard from my priest that it would be all right in the long run, I still felt a certain loneliness when it came to this part. Every Sun- day morning as I would push and shove the kids into clothing and shoes and coats, I would wonder if I was doing something ultimately harmful to my marriage by becoming Orthodox while my husband remained staunchly skeptical of organized religion as a whole.

I was not raised with the “head of the household” refrain in my ears. Twelve years of Catholic school and I can’t recall ever hearing that phrase or concept. My introduction to this idea came through Dave and the Protestant circles he frequented. He was a former Nazarene, and when we met, he attended a popular, upbeat nondenominational church in Chicago. I was suspicious. I thought he was too straitlaced for me. I’d never dated a “born-again Christian.” Agnostics and Catholics were more my bag. I don’t think it was a choice I made, to lean toward agnostics and Catholics, as much as those were the people I met, and it happened that for the most part even the agnostics I dated were former Catholics. We spoke the mother tongue together. It was dysfunctional even as it was comforting. When Dave and I met, I wasn’t going to church anywhere. I still considered myself a Christian mainly because I still fully believed the Creed. I had an understanding with God. I liked Him a whole lot. We talked every day, many times in fact. I believed in the reality of the Holy Spirit. I believed Jesus was who He said He was. I had no trouble with this. I had issues with churches.

Angela Doll Carson

I was on the outside and I kind of liked it that way. Moving away from home was exciting; moving away from my family faith was an adventure. I’d never really been to a Protestant church. It didn’t even occur to me to try it. I guess I figured I’d just wander back into the Catholic Church when things lined up somehow. I was on a self-directed sabbatical from organized religion. I was the prodigal, but I always knew where I lived. I knew I could go home again when the time was right.

I was never the younger son in the story of the Prodigal. I had always been more like the older son who stayed home and did what he was meant to do. I would feel angry when Father Boyle would read the story to us in religion class, knowing full well I was missing the point he was trying to make, that God waits for us, that He sees us coming when we are still a long way off on the road. I was always more like the older son, responsible and angry, ready to rebel but too sensible to do it with anything more than passive-aggressive statements. For as rebellious as I felt as a teenager, I admit I was more afraid than adventurous. Each act of rebellion was measured and calculated. I did not jump off into the chasm but stayed on the spongy ground of the cliff above.

The difference between the Prodigal’s family and mine is that the younger son left a home that stayed grounded and fertile. My home was transitional with my parents’ divorce, torn up into pieces and glued back together on a regular basis. The glory of our family was that we found our way back to one another after each rip in the fabric of us. We were an emotional patchwork in progress, and I like to think I knew that somewhere deep inside. My teenage self was seething and angry, but she was protective and pragmatic enough to keep from adding to the frayed edges of our family struggle.

When our dating turned serious, Dave asked me point- blank what I believed where faith issues were concerned, and I told him. He asked what I thought about Jesus and I said, “Um . . . I like Him?”

He persisted, “Yeah, but do you think He was the Son of God?” and I said, laughing, because it was a ridiculous question to me, “Of course.”

His last hesitation exposed his Nazarene roots a little.

“What do you think about Mary?”

I thought about that for a moment. “I like her too.”

“Yeah, but do you worship her?”

I’d had so little contact with the Protestant culture, I didn’t realize this was a concern for anyone. The question was confusing. “Catholics don’t worship Mary,” I replied. All this served to ease his reservations about asking for my dainty hand in marriage, I guess, because not long after that he did propose to me in the back of a police car.

He ’d borrowed my car that morning and picked me up later to have some lunch and retrieve his car from the shop. That he asked me to drive might have been a tipoff that something was up. He hated my driving, and I admit it’s not without cause. I’m a terrible driver. But I followed his lead and took the wheel. He pointed the turn out to me almost too late, and I squealed my wheels to make the turn. The police car parked across the street pulled out from the curb and made the turn as well.

I had not had a ticket since I was 16, when I was caught doing 65 in a 35 zone, so the thought of breaking my law- abiding streak was unsettling. I turned down the alley to get to the parking lot of the taco joint and the police car turned too, his lights and siren kicking in, a voice on the speaker instructing me to pull over. I chose my spot, kept my hands on the wheel, and blamed Dave for it.

The policeman was a dark-haired, bulky South side cop, and when I rolled down the window he asked for my license and registration in his thick Chicago accent. I handed it to him with shaking fingers, and he showed me his “hot sheet” for the day. My plate was listed there because, as he asserted, a car bearing that plate had been used in connection with a jewelry store robbery that morning. It did not occur to me that Dave had borrowed my car that morning, but he gave me a strange look when the policeman said it.

The cop had us step out of the car and told me he needed to search my car for evidence. I had watched too many episodes of Cops and I was beginning to growl about being unjustly accused. I insisted I was within my rights to watch him search the car and I edged out, leaving Dave with his hands placed flat on the hood of the car.

While the policeman rifled through the empty takeout containers and brown paper bags in my powder blue Hyundai, I watched and saw him slip something into one of them. He walked around to where I stood and pulled a heavy black revolver from the bag. He asked,

“Is this yours?”

I panicked inside but said, almost calmly,

“No, I saw you put that in there.”

He reached into the bag again and pulled out a small velvet jewelry box, saying,

“What about this?”

In my best indignant voice I responded,

“I have never seen that before in my life.”

He suggested we head downtown and I agreed, angry and defiant and ready to assert every known right I could pull from the long-gone days of playing the prosecuting attorney for the mock trial team in high school. He put me into the back of the squad car, and before Dave could follow I heard him say to the policeman,

“Sir, I can explain.”

They closed me into the back of the police car, and I watched as Dave waved his hands, trying to explain away what had become a very strange lunch date. After a few minutes, the policeman opened the door and Dave got in. He leaned forward, talking quickly.

“Listen, I made a deal with the cop. You can either spend the rest of your life in jail,” he said, pulling the box from his pocket, “or you can spend the rest of your life with me.”

I gave the proposal a moment to sink in before I began to beat him about the head.

I got to know some of Dave ’s friends and began to visit his nondenominational church in Lincoln Park as I moved into the Protestant-church–visiting part of my religious journey. I never did find my groove there, though I did try. I wrote and per- formed songs a couple of times for the churches we attended. I joined the choir and the worship team at the Vineyard church. I wrote dramas for the nondenominational church. I helped with the children’s ministry at the Presbyterian church.

No matter how I tried, there was always an empty piece for me. It was as though I was holding a space for that deep holy practice I used to know. I got affirmation of my creative work and acceptance from my peers; there were moments of connection at each of these churches, surely, yet there was something empty there, in me, some vitamin I was missing though I was barely aware of it. All I could do was to follow Dave and try my level best to be a part of it all without losing myself.

My greatest fear has always been that I might lose myself. I don’t know if it stems from a deep wound at an early age or if I simply have this inborn desire to be special, to be set apart. Probably it is a combination of the two. In any case, it is a fear I have had to navigate with each life change I encounter. Entering high school, starting college, dating, moving to a new city, taking a new job, getting engaged, getting married, career choices, having children—all of these things lead me inevitably to the question, “Well, now who am I?”

My response in each of these situations was to try to be different—become a punk rocker instead of listening to Journey, be the only Music Composition major in the music program in college, date only outsiders and weirdos, move to Chicago with my band instead of finishing school in Ohio. Maybe even dating a Protestant was a mild rebellion against my Catholic upbringing. Despite my best efforts, I found I might have lost myself even so. Then when Dave moved away from organized religion just as I began to find my way home through Orthodoxy, the constant refrain piped up in me,

“Well, now who am I?”

I’d like to say that I fully believe he ’ll end up Orthodox one day, but I can’t say that. I just don’t know, and I don’t want it to matter. I worry more that I won’t care, and that not caring means something dark and disconcerting about my heart, about our relationship. I want to care but I don’t want to push. If there is anything I have gleaned on this long and dusty life road so far, it is that we are all moving at our own pace, that our traveling companions and our conversation partners merge or move on or fall back, that we recognize ourselves in the landmarks we pass and the company we keep.

Sometimes we sit on the side of the road and wait for whatever comes next, sometimes we lead, sometimes we follow.

Angela Doll Carlson is a poet, fiction writer and essayist whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in Apeiron Review, Thin Air Magazine, Eastern Iowa Review, Burnside Writer’s Collective, St. Katherine Review, Rock and Sling, “Good Letters,” Ruminate Magazine Blog, Elephant Journal and Art House America. Her memoir, “Nearly Orthodox: On Being a Modern Woman in an Ancient Tradition” from Ancient Faith Publishers is now available at Ancient Faith HERE, and from Amazon HERE. Her next book, “Garden in the East” is expected in 2016.

Angela currently lives in Chicago, IL with her husband, David and her 4 outrageously spirited yet remarkably likable children.

On Going It Alone

Leave a Reply