By Uwe Siemon-Netto

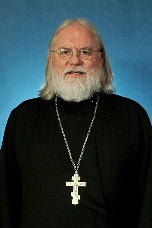

If you stand on the shores of Lake Michigan and watch a man with a long gray mane and beard labor on sailing boats, don’t automatically assume that he’s an aging flower child. He may just be Father Luke, an orthodox cleric, trying to make ends meet.

If you stand on the shores of Lake Michigan and watch a man with a long gray mane and beard labor on sailing boats, don’t automatically assume that he’s an aging flower child. He may just be Father Luke, an orthodox cleric, trying to make ends meet.

Luke, 58, could not even pay his rent with a mission priest’s $1,000 stipend. So he has two other jobs. He works for a boat vendor and keeps book for the Chicago Diocese of the Orthodox Church in America.

Three years ago, when Luke was known as the Rev. Robert Nelson, his material life was easier. Then he was the pastor of Salem, a Lutheran congregation on the South Side of Chicago.

He had a reasonable income then and some 300 parishioners, chiefly black, who loved him and whom he loved.

“Leaving them was the hardest part about converting to Orthodoxy,” he told United Press International Tuesday.

But leave he did, driven by his “search for a spiritual source,” as he described it. Now he is pastor to 30 faithful in Christ the Savior Orthodox Church in the center of Chicago.

Luke is anything but an oddball. In the Midwest alone, the OCA maintains a dozen mission churches among whose priests are four former Lutheran ministers, one former Episcopalian and an Amish.

And if you look beyond, converts are an increasingly important feature in two Eastern-rite denominations in America, the OCA and the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese.

“About half our bishops come from other traditions,”

said Archpriest Leonid Kishkovsky, the OCA’s ecumenical officer.

Kishkovsky ticks off some names: Dimitri Royster, bishop of Dallas, a former Southern Baptist; Seraphim Storheim, bishop of Canada, formerly Lutheran, then Anglican; Pierre (now Peter) Huillier, bishop of New York and New Jersey, a former Catholic from France.

Most stunning perhaps was, in 1996, the conversion of Jaroslav Pelikan, Yale University’s celebrated church historian and Luther scholar. Here is a man who has co-edited 22 of the 55 volumes of Luther’s Works in English, and then late in life he “moved East,” as some theologians like to say.

“I was the Lutheran with the greatest knowledge of the Orthodox Church,” Pelikan reportedly quipped, “and now I am the Orthodox with the greatest knowledge of Luther.”

He is has also been quoted as saying,

“When the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod became Baptist, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America became Methodist, I became Orthodox.”

Presumably, his implication was that the former two denominations were on the verge of losing their doctrinal clarity.

But he does not talk to the media about this move that exemplifies a trend of sorts among some Protestants and Roman Catholics.

“I have received hundreds of requests for interviews and decided not to respond to any of them,” he told UPI Tuesday.

Some former associates say that he simply does not wish to hurt his former Lutheran coreligionists. But a ranking OCA cleric gave a clue:

“Pelikan said he joined us after he had read a work on the Cappadocian Fathers for a fifth time in the original Greek.”

The Cappadocian Fathers were St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, three brilliant leaders of philosophical Christian orthodoxy in the late 4th century.

The study of such church fathers is, of course, en vogue among seekers in the West, who are often disenchanted with Protestantism and with what some call the tainted teaching of modernist Catholic theologians.

Outsiders aver three principal motives for the conversion of Western Christians to Orthodoxy, according to journalism professor and religion columnist Terry Mattingly, a Southern Baptist pastor’s son, who has himself journeyed this way.

“First, people allege that converts are those who could not live without certainty,” he said. “Second, there is supposed to be the attraction of the liturgical beauty, the smells and bells, the icons. “But in my case, the third reason applies: the beauty of the doctrine and faith.”

Purity is what Mattingly’s former pastor, Father Gregory of Holy Cross Antiochian Orthodox Church outside Baltimore, was seeking. Luke, whose congregation, like so many Antiochian parishes in the U.S., consists predominantly of converts, was once Gary Mathewes-Green, an Episcopal priest.

His wife, Frederica, a prolific writer, described in one of her books how he became a “spiritual wanderer,” to use Mattingly’s words.

She wrote,

“It became fashionable to doubt Jesus’ miracles, the Virgin birth, even the bodily resurrection … Gary at last decided he could no longer be under the authority of apostate bishops.”

A meeting with another, by now famous, “spiritual wanderer” ultimately swayed this Episcopal clergyman to become one of 5 million Orthodox Christians in America, Frederica Mathewes-Green said.

That man was Peter E. Gillquist, a former Campus Crusade for Christ staff member, who led more than 2,000 evangelicals into the Antiochian Orthodox Church.

Back in the late 1960s, Gillquist and some friends were “looking for the true New Testament church,” said his wife, Marilyn, who participated in this venture.

“We had become convinced that the church was the means to fulfill the great commission,” he later wrote.

Gillquist and his fellow evangelicals then became, in a sense, forerunners of one particular set of contemporary seekers: the ones who systematically study what most non-liturgical Protestants have been deprived of — the Church Fathers.

“Our background as evangelical Christians meant that we somewhat knew our way backward to the Protestant Reformation, and that we knew our way forward to A.D. 95, the end of the New Testament era,” he wrote.

In other words, they had missed out on what happened theologically between the 2nd and the 16th centuries.

What Gillquist and his friends found out was this: “From the start the church of Christ and his apostles were liturgical and sacramental, with a clearly defined laity, governed by bishops, presbyters and deacons.”

So they founded, in a sense, little orthodox house churches, vested, burned incense, celebrated the liturgy, and became the Evangelical Orthodox Church that was eventually accepted by the Antiochians.

If there is an amazing story about American Christianity in flux, this is it. Here were low-churchmen, whose pastors did not even wear a preaching gown, much less vestments.

Here were people whose churches had a congregational polity and frowned on distant hierarchs. And now they are under the roof of an ancient church whose patriarch lives in Damascus and whose primate in America, Philip Saliba, reigns from Englewood, N.J.

And now Father Peter E. Gillquist is archbishop Philip’s director of Mission and Evangelism, doing what he used to do for Campus Crusade for Christ: gathering souls, except this time for a church where the Apostle Paul had his own conversion experience, which changed him from a persecutor of Christians to the Church’s first and most important theologian.

Leave a Reply