Pierre Haab, a Swiss former Catholic who was disappointed with his religion and was carried away by Buddhism, Hinduism and other screamingly “fashionable” Eastern teachings and who is now a subdeacon of the Orthodox Cathedral of the Exaltation of the Cross in Geneva, speaks about his conversion to Orthodoxy.

by Aviv Saliu-Diallo

—Can you tell us a few words about your family, education and the story of your conversion to the Orthodox faith?

I was born in an under-developed, impoverished, hungry country where the sky is permanently overcast with dark clouds—of course, in the spiritual sense. I am speaking of Switzerland, and especially of the city of Geneva—the center of world freemasonry and finances, the stronghold of obscurantist heresy, and a materialistic megalopolis that is enjoying the lulling, stable comfort that easily protects it from the numerous everyday tragedies of humanity.

I was born in an under-developed, impoverished, hungry country where the sky is permanently overcast with dark clouds—of course, in the spiritual sense. I am speaking of Switzerland, and especially of the city of Geneva—the center of world freemasonry and finances, the stronghold of obscurantist heresy, and a materialistic megalopolis that is enjoying the lulling, stable comfort that easily protects it from the numerous everyday tragedies of humanity.

My parents raised me in the Roman Catholic faith that they had inherited from their ancestors, for which I am extremely grateful to them; they implanted the fundamentals of Christian Revelation in me from childhood—namely faith in God, the doctrine and the necessity of prayer.

We were a practicing Catholic family. We attended Mass on Sundays and major Church feasts, and prayer was a part of our daily life (at least it was so for the first ten years of my childhood). My father, a journalist, devoted his professional life to the protection of the oppressed and justice. As far as my parents are concerned, they did their best to provide the continuity of religious education in our family.

As for the Church, though in my case the more precise name was “Papism”, the situation was different. As a child (in the 1950s) I felt comfortable in that religious environment; for example, I had no problem with prayers in Latin. Although for me faith was “the faith in obedience,” I used to ask many questions, and the adults—my parents and priests—were unable to answer them. And if they did answer me, they did it with a smile and condescendingly, thinking that I was trying to get to the core of the matter too seriously. They gave me to understand that performing the morally required duties was enough for me. And I decided that I would get the answers to my questions later through my independent, in-depth research and analysis of the primary sources, where the morals come from. Judging by my childhood memories, I always had a thirst for truth.

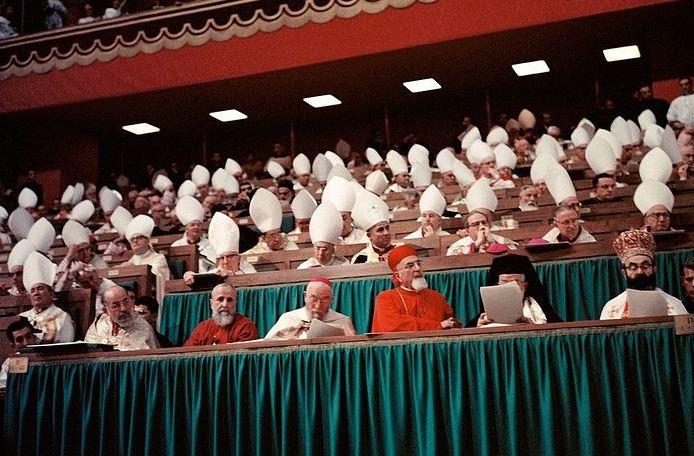

So I was waiting for some changes, when, at the very dawn of my youth, a crucial event happened in the West—a real revolution in Papism (which is still going on today). I mean the Second Vatican Council of 1962. Over a short span of several months (or, in some cases, two to three years) a whole set of rules which had been shaped in the living daily reality of Western Christianity for many centuries, were abolished, declared invalid and obsolete and even partly prohibited; in the twinkling of an eye this heritage was declared the lifeless and dusty relics of archeology. For example, thenceforth during the Mass the officiating priest and the altar were “turned around” and must face toward the congregation; the use of Latin—the centuries-old language of Western liturgies—was banned; the Sunday Mass was moved to Saturday evening—in order to give believers the opportunity to go skiing or sleep more on Sunday morning; the cassock (or soutane)—a non-liturgical garment traditionally worn by Catholic clergy—was declared “unnecessary”; all fasts (the Eucharistic fast, Lent and fasting on Fridays) were abolished; the sacramental wafers are distributed among the faithful by lay people (of both sexes) to “assist” the priest in his “work” and so on.

On the whole, it was an unhealthy thirst for changes. Continuity was no longer supported—it was seen as a sign of death. Instability became the norm, coupled with its main and inevitable consequence—the complacent confidence that thanks to our modern civilization we infinitely surpass all that came to us from the past. In ancient times people were “ignorant churls”, weren’t they? While we are at the forefront of evolution… Or, according to Nietzsche, “‘We have invented happiness,’ say the last men and blink.” The slogan of that revolution was l’aggiornamento, that is, “a bringing up to date”—bringing the Church into compliance with the ever changing world, which presupposes that the Church is condemned to run unendingly after the world.

In this context, I got no answer to the questions I had asked, nor found I any inner guidance.

Thus, little by little, I began to distance myself from the “Catholic” Church. By the way, it coincided with the overall weakening of religious life; before the Second Vatican Council most people (including the most inactive ones), except for inveterate atheists, were involved in the social life of the Church and certainly attended Sunday services. But after the Council the new standard of permissiveness and personal comfort “cleansed” the Churches from the majority of believers.

So a long, very long period of search began for me. Roman Catholicism couldn’t offer me anything essential and it was reduced to vulgar, outward morality, while I blindly kept seeking for answers to my questions.

At the age of seventeen I discovered the book which was like a glimmer seen from the darkness I was in. Entitled The Spirituality of Hinduism and written by a first-rate orientalist, it showed me the existence of a language that expresses the realm of man’s inner reality. Before that time, my experience of spirituality or mysticism had been limited to Papism and my only impressions of it were sentimentalism and outward, superficial morality. This discovery aroused my interest in Eastern religions—firstly, in Hinduism (yoga and metaphysics); and, secondly, in Buddhism, Sufism and esoterics in general.

However, in those same years the Lord vouchsafed me to experience the invaluable gift of providence—the presence of the Russian Orthodox church, the golden domes of which, by the mercy of God, have dominated the city for 150 years. They gave me a sign from my childhood, but I had not been inside it before.

However, in those same years the Lord vouchsafed me to experience the invaluable gift of providence—the presence of the Russian Orthodox church, the golden domes of which, by the mercy of God, have dominated the city for 150 years. They gave me a sign from my childhood, but I had not been inside it before.

For instance, as a college student I ended up at Saturday Vigil there on several occasions. The deep calm of this place, the semidarkness, lit only by candles with the aroma of frankincense and wrapped in the beauty of psalmody—for me, it was an oasis in the desert of this world. The only problem was that I did not understand a single word of what was uttered and sung, so I remained outside the reality of the service, with no means to connect me with it. One time I even attempted to stay at the Divine Liturgy, but, having opened the door, I found myself in front of a throng of people who crowded the whole nave, coupled with choir singers with their loud voices… All of this was so different from the atmosphere at the Vigil that I got frightened, closed the door and left (smiles). Thus, at that period I still was unprepared for my first real meeting with the Orthodox Church.

However, I nevertheless kept searching throughout my studies at university and afterwards. I spent a total of over fifteen years in my quest for the answers to my questions.

Meanwhile, I got married and my wife and I continued this search together. It should be said that several years later, remaining open and receptive to any kinds of faiths, we (out of spiritual honesty and a deep willingness to find the truth) resolved to start studying Christianity more thoroughly. But this time we decided to come nearer to the original sources, which automatically meant the traditions of the Holy Fathers and, therefore, Orthodoxy. And we discovered the language that really blew us away and met our inner expectations.

However, as we had been in delusion for many years, we still regarded non-Christian Eastern traditions as the basis of all spiritual systems, seeing spiritual life through the eyes of a Western consumer at a supermarket, who puts into his basket whatever attracts and interests him in one or another department.

It should also be mentioned that in the 1970s and 1980s a new “spiritualist” tendency was gaining popularity, which seemed to combine the grace of various religions and which can be referred to using the modern term—the transcendent unity of religions. To put it simply, all religions are different only in their outward forms, but they are all the same in their esoteric essence—they have the similar, unique inner spiritual reality, Divine reality. Therefore, all religions are equal. This idea is still popular today, but at that time for young seekers of the truth it was a revelation—an extraordinary and decisive revelation that made things clear, and it was so important for the spiritual development of humanity.

If we consider the esoteric teachings of all faiths as manifestations of the same metaphysical reality, it allows us to change religions depending on the mood or time of day without any contradictions. And if any aspect—moral or practical—seems unacceptable or incomprehensible for your personal vision, then you can label it as “esoteric”; that is, an idea with restrictions intended to respond to the needs of “unenlightened” peoples, which can easily be disregarded. It was very “suitable” and comfortable for an intellectual like me… However, although the wealth of these Eastern teachings allured me, I couldn’t find my place in any of them; they could be attractive, but I did not feel like myself in them.

An opportunity to go to Greece that presented itself right after our wedding played a decisive role in my life. All of a sudden I felt like myself as never before—I felt as if I were in a spiritual family or in my motherland (the things I had always dreamed of), in an emotional and sincere contact with people, in accordance with my principal personal aspirations. It did not take me long to realize that it happened to me because I was in an Orthodox country and the attitude and behavior of people were determined by this reality. We attended the Liturgy where we felt at home—for us, French-speaking people, Greek proved to be more understandable than Russian. After that first meeting we were able to come back there more often, at summer season, and with great joy found the same warm family atmosphere there.

Wishing to find our place in a religion in which we could live to the very roots of our being, not just intellectually, we made an attempt to “return” to Christianity, but in its local, Western form, instead of Orthodoxy (although it does exist in Geneva). Questioning its “honesty” and “truth”, we presumed that not turning to what I then considered to be “the exotics” was more in line with the “obedience”. But it proved absolutely impossible for me to return to the official Papism, notwithstanding my voluntary attempt (due to the reasons stated above).

It was at that same moment of our deep spiritual crisis that my uncle and aunt (who suffered from the extinction of Catholicism themselves) offered us their support—just by their intimate, familial presence in our protracted state of perplexity. Thus, they introduced us to “Catholic traditionalists”—those who did not accept the reforms of the Vatican II and continued to practice the older form of this religion. There, we found the environment that was more focused on spirituality, which created the conditions for practicing piety. But we felt uneasy theologically, having previously opened our hearts to the Orthodox tradition (to say nothing of our inclination for Eastern religions). We got into a situation that could be characterized as “juggling”; we followed Catholic rituals in practice, thought (as we believed) within the framework of the Orthodox theology (we read the Creed without Filioque) and even accepted non-Christian traditions. Though there was no equilibrium in it, the situation full of compromises did not discomfort me, an intellectual. And it could last very long, but at a certain moment the grace of God suddenly intervened in order to make me pass from the realm of ideas to reality, to real life, which was not only a choice of mind but a concrete direction of all my being.

Then I was thirty-two, my wife was expecting our first baby, and we had to make a decision that would determine the entire life of this new little being.

We decided to baptize our daughter. But in which Church? In Papism? It was inconceivable. To traditional Catholicism we were in the status of “recreants”, “protectionists”, “fighting a rearguard action”, who defended the values of the past and were seen as a sect for an outsider. An adult could take it upon himself to belong to that status, but for the harmonious spiritual development of a child it would have been unfavorable and harmful.

So only Orthodoxy was left for us. Inwardly we agreed with it, but we were still separated by the barrier of the language. With the help of two French-speaking parishioners of the Russian church we succeeded in familiarizing ourselves with and going into the heart of the fundamental practical aspects of Orthodoxy. Meanwhile, the sacrament of Baptism was drawing nearer. And, while all was supposed to go easy and without problems, I felt as if paralyzed. Ironically enough, despite my theoretical oneness and harmony with the Orthodox teaching, the power of this action (or, rather, the fear of my losing this comfort of religiosity with “multiple choices”) prevented me from making a concrete step. It was like a situation when somebody walks around a swimming pool again and again and dares not jump in. It was another proof of the fact that the true religion is not about choosing one of many intellectual positions, but choosing life in all its fullness.

The birth of our child impelled us to pass from theory to reality, so we made this step and “jumped” together with our daughter by entering into the family of the Church—and glory be to God for all things! The door to real life has been opened to us ever since.

—What brought you to the Orthodox faith?

I have largely answered this question above, but I can supplement my story and specify some moments.

We were received into the Orthodox Church on Bright Saturday and on the following day, St. Thomas Sunday, we took Holy Communion for the first time. After the Liturgy our friends (a married couple), who had been with us through the whole period of trials, invited us for a cup of coffee. And there, in the quiet of that peaceful place, half seriously and half jokingly they asked us, “What has inspired you to embrace Orthodoxy?” And it was then, when I had just taken Communion—the highest of the Church Sacraments, that I realized the fundamental changes that began to occur inside me. For the entire long period of over fifteen years, when I was wandering in search of answers to my questions, clarity and the place where I could find a spiritual haven, I was permanently under influence of the “centrifugal forces” that distracted me, demoralized me, prevented me from developing and substantially and steadily growing. It seemed that my wanderings and turmoil were endless; I was “carried by all kinds of winds” which gave rise to the sense of instability, anxiety, and nervousness along with vulnerability that left me at the mercy of external influences of all sorts. And it was the extremely abundant grace of God that helped me realize this at the very moment when I was answering their question. “We feel that now we are at the center!”

It is a priceless gift and the answer to my long and painful expectation that God granted me in all its fullness. The stable and sudden grace worked in me very simply yet at full power.

One more change: Before becoming Orthodox I was wary of the veneration of icons. I thought that this action was too concentrated on sensual experience. My approach to acquiring the knowledge of God was based on intellectual activity, and there was almost no space left for sensual experience—I perceived it as a deviation from the purity of the doctrine and “the heaviness of flesh”. As soon as I was received into the Orthodox Church I kissed icons “in obedience”. I came up to the Kazan icon of the Mother of God, which earlier had seemed “unfit” for veneration—Her veil had seemed too “heavy” and “Baroque”, and had provoked a restrained reaction inside me. And now, as I was approaching this icon in order to venerate it, I once again felt a stream of love flowing toward me directly from Holy Theotokos—it was filling my heart and thus it made that barrier disappear forever, just as ice melts because of the presence of a source of heat, or a closed window opens; since then I have perceived all icons as doors to the invisible.

It was accompanied by the sense of centrality that I described above. Indeed my entry into the Orthodox Church opened my heart so that it could be the way the Lord created it: the center of man and the organ through which God and creation become known (and not only the “hotbed” of our emotions to which we often reduce it in our secular life). Of course, my heart “opened” and “grew” gradually, in accordance with the pedagogy of the Church that guides Her children throughout their lives—by the breath of the Holy Spirit, the liturgical teaching and the life of love shared by all Her members.

And in this respect I experienced a significant phenomenon in the first year of my life in the Church: I found “the foundation in Orthodoxy”, but, involuntarily, began to feel not completely united with it, as if a part of me that had been formed in Papism was still lagging behind and observing how my other part conformed to Orthodox rites. This situation of incompleteness vanished a year later by the mercy of God, and at that moment one intensive and living image was sent to me: I felt as if I were a plant which was being grown in a small pot, separately from real soil, while its roots developed and twisted together as they grew, resting against the pot’s sides (it symbolized my position in Papism with its limited doctrine, which was cut off from the fullness of the Church). And then the plant was bedded out and I began to feel earth, that is—the reality of life that is granted abundantly in Orthodox Revelation. However, as is common in the practice of gardening, a plant taken out of the pot retains its “root-knot” unchanged for one full year after that (even if it is transplanted), before taking root, so that they might become stronger and feed in the ground. And, indeed, a year later I felt that I was deeply rooted in eternal life, from which I had previously been separated by numerous obstacles. Thus, I had to live through one full liturgical cycle in order to feel one hundred per cent Orthodox!

Summing it up, I can say that God, through His inexpressible liberality, has given me and continues to give me every day the things I longed and thirsted for—namely the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

—What similarities and differences between Orthodoxy and other religions do you see?

What concord hath Christ with Belial? (2 Cor. 6:15)!

God Himself, the second Person of the Holy Trinity, became incarnate—the true God and the true Man—in order to save mankind after our fall, and He gave us His Body, the Church, whose Head He is. He is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. And you can really experience these three realities, which form one reality, only in the Church.

Beyond all argument, in other religions you can find outward forms of piety, mysticism and examples of faith that are worthy of admiration and praise. (As for heterodox heresies—those of Papism and various branches of Protestantism—they are distortions of the truth, which sadly often look like caricatures of the truth or even blasphemies). Similarly, you can find tenets and rules in them that comfort your intellect, regulate your everyday behavior existentially, and introduce balance into your daily routine.

Although in non-Christian religions you can find wisdom, peace and compassion, they are only relative wisdom, peace and compassion—everywhere you feel lack and even absence… And, first of all, the absence of Christ, for only His fullness can fill all—earth, heaven and hell.

For example, love for your enemies in Christianity is more than just a moral directive or a commandment. Within any religious teaching one can develop the ideas of compassion towards your neighbors or rejection of egotism or hatred—but all of these are only moral norms or standards of conduct. In Orthodoxy, it is a commandment of God and a Revelation of Christ Himself, which you need to cultivate unceasingly and make an effort, and which may become a reality only because it is an implication of the Divine Revelation, of which it was said: God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners (Romans 5:8), and because God gives us His grace.

Likewise, it applies to forgiveness (which is inseparably linked to love for enemies) as well: this distinguishing characteristic of Christianity becomes possible and real only because the True Living God is a Person. Only a person can forgive another person, while a principle or a cosmic law are incapable of doing that. And this mystery reveals our true nature to us—the nature of a person, not just “an individual”, or a mere “set of biological parameters and impulses”; the nature of a living creature that acquires its reality in the fullness and its identity in the relationship with the only True and Living Man, Who out of His love gave us life.

Of course, we could discuss this theme for ages. But in order to summarize the results it is sufficient to state that the specificity of the Christian Revelation, compared with all other “religions”, is that it has as its cornerstone the mystery of the person (to which one of our contemporary saints, Father Justin Popovic, referred as to deserving of the highest esteem and admiration).

Dwelling on this principle, it would be edifying to point out that “Knowledge”, or gnosis (the foundation and nature of all Eastern teachings and basic ideologies that appear under the guise of all sorts of “spiritualities” and claim to have originated from the most ancient “mysteries” of the past—philosophical teachings under the aegis of a “teacher”, theosophy, freemasonry, neo-paganism and other kinds of esoteric and “primordial traditions,” all of which are related to “Hellenic wisdom”), becomes the basis for a contradiction of the position of “modern man”. In fact it is one of the worst paradoxes, which makes you believe in the possibility of “gaining freedom” through the knowledge of “the secret doctrine”—listening to the hissing of the serpent from the tree with the same name, saying,

Ye shall be as gods (Gen. 3:5)

—which returns again in the determinism of the same “cosmic laws” and aerial powers that Christ came to free us from.

This myth of gnosis is in fact as old as the serpent itself; the “Knowledge” will bring you “complete liberty” (even from the Creator!), and man will become his own master. Among other names, this tree with the serpent on it, in many Eastern teachings has the name “kundalini”; a climb on this tree will involve the “initiation” by “secret spirits” and “enlightenment”, that is—acquiring absolute and ultimate knowledge. The satan’s hook today is as poisonous as it was in the Garden of Eden. It must be said that, “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” introduces you to two concepts belonging to the realm of abstract ideas and leads you to the world of dualism, while relations with the Living God and the Truth preserve your integrity—you remain interconnected both with the world and with Him Who can say:

I am that I am (Exod. 3:14).

Nevertheless, as knowledge is good, for it is the foundation of Christian Revelation, so ignorance is described by many Church Fathers as “the cause of all vices”, “the mother of all evils”, “the worst of the mental diseases” and so on, because, according to Christ, And this is life eternal, that they might know Thee, the only True God, and Jesus Christ, Whom Thou hast sent (Jn. 17:3). These words mean getting to know the existing relations between man and his Creator, not imagining yourself independent from all and your own “god”. But this knowledge can be acquired only through the Church sacraments and personal asceticism, and, as St. Justin Popovic rightly put it,

the Word of God contains the dynamic and metaphysical principle of knowledge.

We could meditate on this theme at least in order to remember how Western man was driven by the unhealthy, insatiable lust for knowledge over many centuries—from the “Renaissance” of paganism to “Enlightenment” and positivism; this reached such an extent that even an ordinary, incontrovertible, absolute truth inevitably boils down to the following expression: “It is a scientifically substantiated fact.” In other words, it is “the truth”, “absolute and incontestable”, which reduces to a ‘subjective impression” all that is disclosed by God in Revelation (although science regularly reconsiders its own findings and admits itself that absolute objectivity does not exist, that impartiality depends on an experimenter’s position—but that’s a whole different story).

Let us remind the readers that man existentially needs faith, faith in something or somebody as the last refuge that allows him to find a reference point. Thus, so-called “science” offers him a favorable advantage by providing a false “truth” that is “ready for use” and freeing him from the need for reflection; that is—a personal experiment, unlike Christian Revelation, which demands ascetic life from each one of us. In other words, we have to change of our way of life, without which the truth that is given to us can be neither ours nor real.

In Orthodoxy, the Revelation of the mystery of our salvation is given us in theanthropic form—by God Who became a Man—not by an avatar of the Hindu or Monophysitic type where a god only takes a human-like form; nor is it through “spiritual exercise” when someone through his own efforts achieves “enlightenment”, which sets him free from the cosmic laws of cause and effect.

The reality of Christian truth in the etymological sense of the word, namely what is beyond the human speech, what cannot be adequately explained and expressed with human words—is that God is no cosmic principle (transpersonal and anonymous), but is a “Philanthropos” (Who loves mankind), that He is essentially the Friend of humanity, and that He proved to be True God and True Man (the only True Man) Who is unto the Jews a stumblingblock, and unto the Greeks foolishness (1 Cor. 1:23). This kenosis—the self-deprecation and self-humiliation of God Who became Man—is absurd for the Creator, while taking on human flesh (which is like a prison) and glorifying it through the Resurrection is nonsense for a spirit that was “freed”.

Orthodoxy is the divine life into which Christ, the God-Man, enters in His Body, that is—the Church.

There is no other place where you can find this life.

Orthodoxy is not a religion. Orthodoxy is divine life.

—Can you tell us about religious life in Switzerland?

There is still an extremely high level of religious tolerance in Switzerland, and I don’t think I have a right to say more about it. As for Orthodoxy, over the past thirty years by the mercy of God several new churches have appeared to serve the needs of immigrants and converts. However, all immigrants and converts are just a small minority and they don’t warrant opening new churches.

If Geneva, Vevey, Bern, Zürich or the Holy Trinity Monastery in Dompierre have their own churches with a possibility of holding regular services, other places can neither hold regular services nor acquire ownership of a place for public worship, and so they have to lease their premises or partake of the hospitality of some non-Orthodox parishes.

It is obvious that in Western countries like Switzerland, Orthodoxy is seen as a “foreign” religion and something exotic. For example, in Geneva (in view of the fact that Switzerland is a confederation) public religious events, such as processions or ringing of bells on the Holy Paschal night according to the Julian calendar, are banned. All in all, against the background of a still rather restrained religiosity in secularized Western countries like Switzerland, and the increasing de-Christianization of modern European societies, Orthodoxy is treated with relative tolerance, as long as it is not involved in current political events… It is still so.

—Can you share information on the Orthodox church in Geneva where you now serve?

The Russian Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross is the first Orthodox church in Geneva, and has existed there by the grace of God already for 150 years. Thus, till the second half of the twentieth century it played a key, uniting role for Orthodox believers and immigrants of various jurisdictions represented in Geneva. In 1946, the Patriarchate of Moscow built the Church in honor of the Nativity of the Most Holy Mother of God (despite the strained relations with ROCOR at that time), and in the early 1970s the Greek Church of St. Paul of the Patriarchate of Constantinople was built. Then it was continued by the establishment of two Romanian parishes.

However, today, in spite of the use of Church Slavonic as the major liturgical language, our church is continuing its mission of receiving foreign newcomers of different nationalities along with immigrants from Russia, whose number has been increasing for twenty years. Our parish life is very active (for children and lay adults alike, including the organization of pilgrimage trips to local holy sites).

I am greatly indebted to this church for receiving me into Orthodoxy and I am eternally grateful to the Lord for granting me the opportunity to serve as a subdeacon despite my unworthiness. I pray that He will send this church His abundant blessings in the future as well.

—What would you like to say to our readers in conclusion?

Orthodoxy is the Church, the most precious gift of God to mankind—a priceless pearl, a hidden treasure given to the human race so that we could enter the Kingdom, that is—life eternal, through communion with the Body of Christ and the knowledge of God.

Saints can achieve this already during their life on earth; but in any case this infinite knowledge and Revelation of God can have no end, and only eternity can be their measure.

If it were necessary to prove again that Orthodoxy is the life that opens up through the True Life, and not one of numerous teachings belonging to the realm of archeology, then the holy fathers would instruct us today with the same sermons as in the first centuries of Christianity. Words of the holy fathers of our times bear the same witness as the words of their predecessors; miracles continue to occur nowadays just as they did in ancient times; and the previous century, among the other martyrs and confessors, produced holy doctors and elders, “fools for Christ” and wonderworkers, who are continually helping us through their intercessions.

From the perspective of our time, the Church has been subjected to specific attacks of the enemy at each period of Her life, and today Orthodoxy (which has always been the target of the evil one) is experiencing attacks from the world—implicit and unceasing. It partly occurs through force, as in the deployment of the largest American overseas military base in Kosovo, which became the culmination of the demonization of Serbia during the war there, orchestrated not only by armies but also by the Western media (this is precisely what Orthodox Christians in Ukraine are experiencing now). The economic war that is aimed at depriving Greece of its national identity and using it only for the needs of a neo-liberal economy has been orchestrated the same way as well.

The persistent struggle aimed at destroying the values of Orthodox organizations under the mask of “progress”, “evolution”, and “westernization/globalization” is even more sophisticated and crafty by nature. Anyway, whether it be visible or invisible violence, from time immemorial Orthodoxy has been regarded by the West as its enemy that must be destroyed; it is no coincidence that during the war in former Yugoslavia a senior politician in Austria openly declared in Brussels,

“Europe ends where Orthodoxy begins.”

The most insidious and destructive strategy is being pursued within the Church Hierarchy, through those of whom it was written in the Bible: the builders that rejected the cornerstone (see Ps. 118, 22), in order to sow (under the mask of development and openness) ideas and views that are inconsistent with Revelation.

All the saints of our times have warned us against this danger, and condemned the most pernicious “pan-heresy” [an allusion to ecumenism—ed.]—the failure to remain faithful to the teaching of the Fathers in order to follow “the wisdom of this world” and “the spirit of the age”.

However, modern man, even an Orthodox Christian, thinks that he is spiritually “more developed” than people of the previous epochs. In his view, the fact that Sts. Mark of Ephesus, Cosmas of Aetolia, Ignatius (Brianchaninov), Seraphim (Sobolev), Paisios of Mt. Athos, Gabriel of Georgia and many others described ecumenism as the most dangerous heresy stems from their “too narrow view” of Orthodoxy; or maybe these people were “not developed enough” intellectually and socially—for we have made a great progress since that time, haven’t we?

In order to attain his object, the father of lies stoops to distorting the greatest truths. Hiding behind the mask of “charity” and love for one’s neighbor, he wants the Church to “be opened up”, in other words, to become “relativistic” and be reduced to “one of the denominations”. However, the Church Fathers were unanimous in their teaching: we must love the sinner and hate sin. Let us not be mistaken: Jesus Christ the same yesterday, and to day, and for ever (Heb. 13:8), His teaching is living and has nothing to do with archeology, nor is it dependent on the environment of the past century. True, we have lived in the situation described by Apostle Paul for a long time: For the time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine; but after their own lusts shall they heap to themselves teachers, having itching ears (2 Tim. 4:3).

Orthodoxy is a Revelation that every human life is a gift from God. It is a mystery beyond our comprehension, and it is in love that it finds the answer. It is a mystery, and not a dangerous product of Darwinian biological “evolution” (continually “groping its way”), which allegedly took us on a very long journey from one-celled protozoa to apes that became our supposed “ancestors”; nor is it a “meaningless blind chance” that is moving towards its end (the end of human life) at a fast pace, which is no less absurd in its total nonexistence; nor is it just one in a long line of rebirths (reincarnations)—a “convenient” idea for explaining (and very primitively) the causes of misfortunes and injustices that we encounter in our life in the world based on the laws of mechanics, thus moving us further away from the real cause.

God gave us life. It means that the Almighty gave each of us our beginning, birth from nonexistence, and this life will have no end. And indeed we will need eternity in order to give Him praise and thanks for this priceless, immeasurable gift.

Glory to God for all things!

Leave a Reply