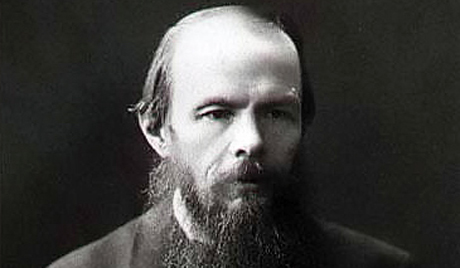

On February 9, 1881, Feodor Dostoevsky parted this world as his family read to him the Gospel parable of the prodigal son. This article in Orthodox America from the 100th anniversary year of Doestoevsky’s death commemorates the great writer, and shows his significance to the Orthodox Church. his work is exceptionally timely for us here in the United States today.

* * *

January 28/February 9 of this year (1981) marked the hundredth anniversary of the death of Fyodor M. Dostoevsky, the great Russian writer who was probably the most powerful Orthodox voice in the world literature of recent centuries. In marking this anniversary with an Ukase decreeing the celebration of memorial Services for him in all dioceses, as well as recommending gatherings and lectures devoted to him, the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Church Outside of Russia noted that

“his creative activity was highly valued by outstanding church thinkers. His burial is remembered as an extraordinary event, and in the name of the St. Alexander Neysky Lavra (in Petersburg) his widow was asked to bury him precisely there, since Fyodor Michailovich was a defender of Orthodoxy.”

Unlike most Russian novelists and writers of the 19th century, Dostoevsky’s intent in his creative activity was precisely to exemplify Orthodox principles. After a youthful fascination with Western ideas and his involvement with a socialist-revolutionary group, Dostoevsky returned from a term of exile in Siberia fully converted to the truth of Orthodoxy and resolved to use his literary talent to defend this truth against its many enemies, and to illuminate with its light the spirit of his times.

In The Possessed (literally, “The Demons”,), he made a devastatingly precise analysis of the radical revolutionary mind and foresaw the hundred million people it would be necessary to kill to make the revolution successful in Russia (Solzhenitsyn has noted the exact correspondence to the number of victims of Soviet Communism).

In Crime and Punishment he traces the effect of the philosophy of nihilism (the foundation of the revolution) on one person’s soul, and its salvation by Christianity.

In “The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” in The Brothers Karamozov, he set forth the difference between the Western. distortion of Christianity and true Orthodoxy, and in The Diaspora of a West he showed further the underlying unity of papalism and socialism and their ultimate merger in the reign of Antichrist.

In these and other books he laid bare the intent and the final goal of modern secular humanism: a society without God. He expressed the “theological” definition of this goal several years before Nietzche in the West: There is no God (or: there is no immortality), therefore everything is permitted.

But unlike Nietzche, whose inability to believe drove him insane, Dostoevsky with his diagnosis gave also the answer to this modern sickness of the soul: a return to the fundamentals of Orthodox Christianity.

Dostoevsky was a passionate man and had many falls and mistakes. But he is remembered as one who, being a thoroughly “modern” man who had come to see the “one thing needful” in life, offered a sincere struggle against his passions and helped us all to see more clearly the nature of the workings of passion and sin in fallen man. Elder Ambrose of Optina said of Dostoevsky, after he visited the monastery, that he was

“one who is repenting.”

Thus he is closer to today’s Orthodox converts than many more perfect men, such as the great Russian ascetics of the 19th century, and can help to open up to them the way to the saving truth of Orthodoxy. Above all, his compassionate portraits of the suffering and downtrodden, and even of those possessed by passions, can help Orthodox converts to develop the basic Christian concern and compassion which are so often lost sight of in our overly intellectual times.

It’s a great.gft to find myself in the Church of the second Russian writer to imprint my soul so powerfully : ‘I overcame an objection,’ he remarked of his atheist opponents, ‘that they could scarcely conceive if.”