Part Two

Tradition, Martyrdom, Stillness

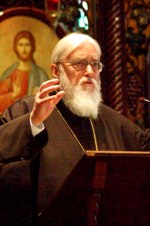

by Bishop Kallistos (Ware), Bishop of Diokleia

As I deepened my knowledge of Orthodoxy, three things in particular attracted me and held me fast. First, I perceived in the contemporary Orthodox Church — despite its internal tensions and its human failings — a living and unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles and Martyrs, of the Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils.

As I deepened my knowledge of Orthodoxy, three things in particular attracted me and held me fast. First, I perceived in the contemporary Orthodox Church — despite its internal tensions and its human failings — a living and unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles and Martyrs, of the Fathers and the Ecumenical Councils.

This living continuity was summed up for me in the words fullness and wholeness, but most of all it was expressed by the term Tradition. Orthodoxy possesses, not through human merit but by God’s grace, a fullness of faith and spiritual life, a fullness within which the elements of dogma and prayer, of theology and spirituality, constitute an integral and organic whole. It is in this sense the Church of Holy Tradition.

In this context I would like to put especial emphasis on the word “fullness.” Orthodoxy has the plenitude of life in Christ, but it does not have an exclusive monopoly of the truth. I did not believe then, nor do I believe now, that there is a stark and unmitigated contrast between Orthodox “light” and non-Orthodox “darkness.”

We are not to imagine that, because Orthodoxy possesses the fullness of Holy Tradition, the other Christian bodies possess nothing at all. Far from it; I have never been convinced by the rigorist claim that sacramental life and the grace of the Holy Spirit can exist only within the visible limits of the Orthodox Church. Vladimir Lossky is surely right to maintain that, despite an outward separation, non-Orthodox communities still retain invisible links with the Orthodox Church:

Faithful to its vocation to assist the salvation of all, the Church of Christ values every “spark of life,” however small, in the dissident communities. In this way it bears witness to the fact that, despite the separation, they still retain a certain link with the unique and life-giving center, a link that is — so far as we are concerned — “invisible and beyond our understanding.” There is only one true Church, the sole bestower of sacramental grace; but there are several ways of being separated from that one true Church, and varying degrees of diminishing ecclesial reality outside its visible limits. [Vladimir Lossky, introductory note to the article of Patriarch Sergius of Moscow, “L’Église du Christ et les communautés dissidentes,” Messager de I’Exarchat du Patriarche Russe en Europe Occidentale 21 (Paris, 1955), 9-10].

Thus on Lossky’s view, which I willingly made my own, non-Orthodox communities continue in varying degrees to participate in the Church’s life of grace. Yet it still remains true that, while these non-Orthodox communities possess part of the saving and life-giving truth, in Orthodoxy alone is the fullness of that truth to be found.

I was particularly impressed by the manner in which Orthodox thinkers, when speaking of their Church as the Church of Holy Tradition, insist at the same time that Tradition is not static but dynamic, not defensive but exploratory, not closed and backward-facing but open to the future. Tradition, I learnt from the authors whom I studied, is not merely a formal repetition of what was stated in the past, but it is an active reexperiencing of the Christian message in the present. The only true Tradition is living and creative, formed from the union of human freedom with the grace of the Spirit. This vital dynamism was summed up for me in Vladimir Lossky’s lapidary phrase:

“Tradition … is the life of the Holy Spirit in the Church.”

See “Tradition and traditions,” in Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons (Olten, Switzerland: Urs Graf-Verlag, 1952), 17; in the revised edition (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1982), 15. This essay is reprinted in Vladimir Lossky, In the Image and Likeness of God (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1974), 141-68; see 152.

Of course Lossky does not exclude the Christological dimension of Tradition, as is clear from the context in which this phrase occurs. Emphasizing the point, he adds:

“One can say that ‘Tradition’ represents the critical spirit of the Church.” “Tradition and traditions,” 19 (revised edition, 17).

We do not simply remain within the Tradition by inertia.

In the eyes of many non-Orthodox observers in the West, Orthodoxy appears as a Church of rigid immobility, oriented always towards the past. That, however, was not my personal impression when first I came to know the Orthodox Church in the early 1950s, and it is certainly not my impression today after being Orthodox for over forty years. Although many aspects of Orthodox life are indeed characterized by a certain archaism, that is very far from being the whole story. On the contrary, what Sir Ernest Barker says of the twelve centuries of Byzantine history can be applied equally to the twenty centuries of Orthodox church life:

“Conservatism is always mixed with change, and change is always impinging on conservatism, during the twelve hundred years of Byzantine history; and that is the essence and fascination of those years.”[ Social and Political Thought in Byzantium (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957), 28].

As the life of the Holy Spirit within the Church, so I discovered, Tradition is all-embracing. In particular it includes the written word of the Bible, for there is no dichotomy between Scripture and Tradition. Scripture exists within Tradition, and by the same token Tradition is nothing else than the way in which Scripture has been understood and lived by the Church in every generation. Thus I came to see the Orthodox Church not only as “traditional” but also as Scriptural. It is not for nothing that the Book of the Gospels rests on the center of the Holy Table in every Orthodox place of worship. It is the Orthodox rather than the Protestants who are the true Evangelicals. (If only we Orthodox in practice studied the Bible as the Protestants do!)

As the life of the Spirit, so Lossky and Florovsky assured me in their writings, I had the happiness of knowing both of them not just through their writings but personally: Vladimir Lossky before, and Father Georges after, my reception into the Orthodox Church. “Tradition is not only all-embracing but inexhaustible. In the words of Father Georges Florovsky:

Tradition is the constant abiding of the Spirit and not only the memory of words. Tradition is a charismatic, not a historical principle… The grace-giving experience of the Church … in its catholic fullness … has not been exhausted either in Scripture, or in oral tradition, or in definitions. It cannot, it must not, be exhausted.” “Sobornost,” 65, 67 (italics in original).

While the period of the seven Ecumenical Councils possesses a preeminent importance for Orthodoxy, we are not for one moment to imagine that the “age of the Fathers” came to a close in the eighth century. On the contrary, the Patristic era is open-ended. There is no reason, apart from human sin, why there should not be in the third millennium further Ecumenical Councils and new Fathers of the Church, equal in authority to those in the early Christian centuries; for the Holy Spirit continues present and active in the Church as much today as ever He was in the past.

This vibrant and vivifying conception of Tradition that I discovered in Orthodoxy made increasing sense to me. More and more I found that the living continuity to which the Orthodox Church bore witness was lacking in the Anglicanism within which I had been brought up from early childhood. The continuity had been impaired, if not broken, by the developments within the Latin West during the Middle Ages.

Even if, for many Anglicans from the sixteenth century onwards, the English Reformation represented an attempt to return to the Church of the Ecumenical Councils and the early Fathers, how far in actual fact could this attempt be reckoned a success? The “Orthodoxy” of the Church of England seemed at best implicit — an aspiration and a distant hope rather than an immediate and practical reality.

I shall never cease to be sincerely grateful for my Anglican upbringing. Never would I wish to engage in negative polemic against the communion where I first came to know Christ as my Savior. I remember with lasting happiness the beauty of the choral services in Westminster Abbey which I attended while a boy at Westminster School, and in particular I recall the great procession with cross, candles and banners at the Sung Eucharist on the feast of St Edward the Confessor.

I am grateful also for the links which I formed, while at school and university, with members of the Society of St Francis such as Father Algy Robertson, the Father Guardian, and his young disciple Brother Peter. It was the Anglican Franciscans who taught me the place of mission within the Christian life and the value of sacramental confession.

I shall always regard my decision to embrace Orthodoxy as the crowning fulfillment of all that was best in my Anglican experience; as an affirmation, not a repudiation. Yet, for all my love and gratitude, I cannot in honesty remain silent about what troubled me in the 1950s, and today troubles me far more; and that is the extreme diversity of the conflicting beliefs and practices that coexist within the bounds of the Anglican communion.

I was (and am) disturbed first of all by the contrasting views of Anglo-Catholics and Evangelicals concerning central articles of faith such as the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the Communion of Saints. Are the consecrated elements to be worshiped as the true Body and Blood of the Savior? May we intercede for the departed, and ask the Saints and the Mother of God to pray for us? These are not just marginal issues, over which Christians may legitimately agree to differ. They are fundamental to our life in Christ. How then could I continue in a Christian body which permitted its members to hold diametrically opposed views on these matters?

I was yet more disturbed by the existence within Anglicanism of a “liberal” wing that calls in doubt the Godhead of Christ, His Virgin Birth, His miracles and His bodily Resurrection. St Thomas’s words rang in my ears:

“My Lord and my God!’ (Jn 20:28).

I heard St Paul saying to me:

“If Christ is not risen, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is also in vain” (i Cor 15:24).

For my own salvation I needed to belong to a Church which held fast with unwavering faithfulness to the primary Christian teachings concerning the Trinity and the Person of Christ. Where could I find such a Church? Not, alas! in Anglicanism. It did not have that continuity and fullness of living Tradition for which I was searching.

What, then, of Rome? In the 1950s, before the second Vatican Council, the obvious course — for any Catholic-minded member of the Church of England who was unhappy about Anglican “comprehensiveness” — was to become a Roman Catholic. Here is a Christian communion which, no less than the Orthodox Church, claims an unbroken continuity with the Apostles and the Martyrs, with the early Councils and the Fathers. What is more, here is a Church of Western culture. Why, then, look to Orthodoxy? Could not my search for living Tradition find its fulfillment much nearer at hand?

Yet, whenever I felt tempted to move Romewards, I hesitated. What held me back was not primarily the Filioque, although after reading Lossky I could see that this was important. The basic problem, however, was the papal claim to universal jurisdiction and infallibility. From my study of the early centuries of Christianity, it became clear to me that Eastern Fathers such as St Basil the Great and St John Chrysostom — and indeed Western Fathers such as St Cyprian and St Augustine — understood the nature of the Church on earth in a manner radically different from the viewpoint of the first Vatican Council.

The developed doctrine of Roman primacy, as I saw it, was simply not true to history. Papal centralization, especially from the eleventh century onwards, had gravely impaired the continuity of Tradition within the Roman communion. Only in the Orthodox Church could I secure what I was seeking: the life-giving and undiminished presence of the past.

My conviction that only within Orthodoxy could I find in its fullness an unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles and the Fathers was reinforced by two other aspects of Orthodoxy that I began increasingly to notice. The first was the prevalence of persecution and martyrdom within recent Orthodox experience — first under the Turks and then, in the twentieth century, under Communism. Here was something that linked the Orthodox Church of modern times directly to the pre-Constantinian Church of the first three centuries. “My strength is made perfect in weakness,”

said Christ to St Paul (2 Cor 12:9);

and I saw His words fulfilled again and again in Orthodox history since the fall of Byzantium.

Alongside those who underwent an outward and visible martyrdom of blood, there have also been countless others in Orthodoxy who have followed the humiliated Christ through a life of inner martyrdom: kenotic saints who displayed a gentle, generous and compassionate love, such as Xenia of St Petersburg, Seraphim of Sarov, John of Kronstadt, and Nektarios of Aegina. I found the same kenotic compassion in the writings of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

Two saints who especially appealed to me — for I had been a pacifist since the age of seventeen — were the Passion-Bearers Boris and Gleb, brother Princes from eleventh-century Kiev. In their refusal to shed blood even in self-defense, in their repudiation of violence and in their innocent suffering, I saw exemplified the central message of Christ’s Cross.

Another aspect of Orthodoxy which I came to value, alongside martyrdom, was the mystical theology of the Christian East. Tradition, I realized, signifies not just the handing-down of doctrinal definitions but equally the transmission of spirituality. There cannot be any separation, and still less any opposition, between the two; as Vladimir Lossky rightly states,

“there is… no Christian mysticism without theology; but, above all, there is no theology without mysticism,” for mysticism is to be seen “as the perfecting and crown of all theology: as theology par excellence[” The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (London: James Clarke, 1957), 9].

Whereas it had been the liturgical services with their rich symbolism and their music that originally drew me to Orthodoxy, I now saw how this “iconic” form of worship is counterbalanced in the Christian East by the “non-iconic” or apophatic practice of hesychastic prayer, with its “laying-aside” of images and thoughts. In The Way of a Pilgrim and the writings of “A Monk of the Eastern Church” — Archimandrite Lev Gillet, the Orthodox chaplain of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius — I learnt how hesychia, stillness or silence of the heart, is attained through the constant repetition of the Jesus Prayer. St Isaac the Syrian showed me that all words find their fulfillment in stillness, just as servants fall silent when the master arrives in their midst:

The movements of the tongue and heart during prayer are keys. What comes afterwards is the entering into the treasury. At this point let every mouth and every tongue become silent. Let the heart which is the treasury of our thoughts, and the intellect which is the ruler of our senses, and the mind, that swift-winged and daring bird, with all their resources and powers and persuasive intercessions — let all these now be still: for the Master of the house has come. Homily 22(23): tr. Wensinck, 112; tr. Miller, 116.

The Church as communion

These three things — Tradition, martyrdom and stillness — were already sufficient to convince me of the truth and relevance of Orthodoxy. But the compelling need for me not only to contemplate Orthodoxy from the outside, but also to enter within, was brought home to me by words that I heard spoken in August 1956 at the summer conference of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius. Father Lev Gillet was asked to define the term “Orthodoxy.” He replied:

“An Orthodox is one who accepts the Apostolic Tradition and who lives in communion with the bishops who are the appointed teachers of this Tradition.”

The second half of this statement — the part which I have italicized — was of particular significance for me. I thought to myself: Yes, indeed, as an Anglican I am at liberty to hold the Apostolic Tradition of Orthodoxy as my own private opinion. But can I honestly say that this Apostolic Tradition is taught unanimously by the Anglican bishops with whom I am in communion?

Orthodoxy, so I recognized in a sudden flash of insight, is not merely a matter of personal belief; it also presupposes outward and visible communion in the sacraments with the bishops who are the divinely-commissioned witnesses to the truth. The question could not be avoided: If Orthodoxy means communion, was it possible for me to be truly Orthodox so long as I still remained an Anglican?

Those simple words spoken by Father Lev created no great stir in the conference at large, but for me they served as a critical turning-point. The idea which they planted in my mind — that Orthodox faith is inseparable from Eucharistic communion — was confirmed by two things which I read around this time. First, I came across the correspondence between Alexis Khomiakov and the Anglican (as he was then) William Palmer, Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford. Palmer had sent Khomiakov a copy of his work A Harmony ofAnglican Doctrine with the Doctrine of the Catholic and Apostolic Church of the East. Here Palmer took, phrase by phrase, the Longer Russian Catechism written by St Philaret of Moscow, and for every statement in the Catechism he cited passages from Anglican sources in which the same doctrine was affirmed.

In his reply (November 28, 1846), Khomiakov pointed out that he could equally well have produced an alternative volume, quoting other Anglican writers — no less authoritative than those invoked by Palmer — who directly contradicted the teaching of Philaret’s Catechism. In Khomiakov’s words:

Many Bishops and divines of your communion are and have been quite orthodox. But what of that? Their opinion is only an individual opinion, it is not the Faith of the Community. The Calvinist Ussher is an Anglican no less than the bishops (whom you quote) who hold quite Orthodox language. We may and do sympathize with the individuals; we cannot and dare not sympathize with a Church … which gives Communion to those who declare the Bread and Wine of the High Sacrifice to be mere bread and wine, as well as to those who declare it to be the Body and Blood of Christ. This for an example — and I could find hundreds more — but I go further. Suppose an impossibility — suppose all the Anglicans to be quite Orthodox; suppose their Creed and Faith quite concordant with ours; the mode and process by which that creed is or has been attained is a Protestant one; a simple logical act of the understanding… Were you to find all the truth, you would have found nothing; for we alone can give you that without which all would be vain — the assurance of truth. Birkbeck, Russia and the English Church, 70-71.

Khomiakov’s words, severe yet just, reinforced what Father Lev had said. By this time I had come to believe all that the Orthodox Church believed; yet the “mode and process” by which I had reached these beliefs was indeed a “Protestant one.”

My faith was “only an individual opinion,” and not “the Faith of the Community;” for I could not say that all my fellow Anglicans believed the same as I did, or that mine was the faith taught by all the Anglican bishops with whom I was in communion. Only by becoming a full member of the Orthodox Church — by entering into full and visible communion with the Orthodox bishops who were the appointed teachers of the Orthodox faith — could I obtain “the assurance of truth.”

A few months later I read in typescript an article on the ecclesiology of St Ignatius of Antioch by the Greek-American theologian Father John Romanides.This article, written while Romanides was studying under Afanassieff at the Orthodox Institute of St Sergius in Paris (1954-55), did not appear in print until several years later: see The Greek Orthodox Theological Review 7:1-2 (1961-62), 53-77.

Subsequently Romanides became dissatisfied with the standpoint of Eucharistic ecclesiology: see Andrew J. Sopko, Prophet of Roman Orthodoxy: The Theology of John Romanides (Dewdney, BC, Canada: Synaxis Press, 1998), 150-53. Here, for the first time in a fully developed form, I encountered the perspective of “Eucharistic ecclesiology” which has since been popularized by the writings of Father Nicolas Afanassieff See N. Afanassieff, “The Church Which Presides in Love,” in John Meyendorff and others, The Primacy of Peter (London: Faith Press, 1962), 57-110 (new edition [Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 19921, 91-143). Cf. Aidan Nichols, Theology in the Russian Diaspora: Church, Fathers, Eucharist in Nikolai Afanasiev (1893-1966) (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1989). and Metropolitan John (Zizioulas) of Pergamum. See John D. Zizioulas, Being As Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1985). Cf. Paul McPartlan, The Eucharist Makes the Church: Henri du Lubac and John Zizioulas in Dialogue (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1993).

On a first reading Father John’s interpretation of the letters of St Ignatius at once convinced me, and when I consulted the actual letters themselves my convictions were fully confirmed.

The primary icon of the Church for St Ignatius, so I found, was precisely this: a table; on the table, a plate with bread and wine; around the table, the bishop, the presbyters and the deacons, along with all the Holy People of God, united together in the celebration of the Eucharist.

As St Ignatius insisted,

“Take care to participate in one Eucharist: for there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup for union in His blood, and one altar, just as there is one bishop.” To the Philadelphians 4.

The repetition of the word “one” is deliberate and striking:

“one Eucharist … one flesh … one cup … one altar … one bishop.”

Such is St Ignatius’ understanding of the Church and its unity: the Church is local, an assembly of all the faithful in the same place (epi to avto); the Church is Eucharistic, a gathering around the same altar, to share in a single loaf and a single cup; and the Church is hierarchical — it is not simply any kind of Eucharistic meeting, but it is that Eucharistic meeting which is convened under the presidency of the one local bishop.

Church unity, as the Bishop of Antioch envisages it, is not merely a theoretical ideal but a practical reality, established and made visible through the participation of each local community in the Holy Mysteries. Despite the central role exercised by the bishop, unity is not something imposed from outside by power of jurisdiction, but it is created from within through the act of receiving communion. The Church is above all else a Eucharistic organism, which becomes itself when celebrating the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper

“until He comes again” (1 Cor 11:26).

In this way St Ignatius, as interpreted by Father John Romanides, supplied me with an all-essential missing link. Khomiakov had spoken about the organic unity of the Church, but he had not associated this with the Eucharist. Once I perceived the integral connection between ecclesial unity and sacramental communion, everything fell into place.

Yet where did this leave me, still (as I was) an outsider, unable to receive the Orthodox sacraments? At Easter 1957 for the first time I attended the Orthodox service at Paschal Midnight. I had intended to receive communion later in the morning at an Anglican church — in that year the dates of Orthodox and Western Easter coincided — but, emerging from the Orthodox celebration, I knew that this was an impossibility. I had already kept Christ’s Resurrection with the Orthodox Church, in a manner that was for me complete and unrepeatable. Had I afterwards received Holy Communion elsewhere, that would have been — for me personally — something unrealistic and untruthful.

Never thereafter did I make my communion at an Anglican altar. After remaining without the sacrament for some months, I was talking in September 1957 with Madeleine, the wife of Vladimir Lossky. She pointed out to me the peril of my situation, living as I was in no man’s land.

“You must not continue as you are,” she insisted. “The Eucharist is our mystical food: without it, we starve.”

Her words were confirmed a few days later by a strange incident that I have never been able fully to explain to myself. I went to the chapel in Versailles where the head of the Western European diocese of the Russian Church in Exile, Archbishop John (Maximovitch) — now glorified as a saint — was officiating at the Divine Liturgy. It was his custom to celebrate daily, and as it was a weekday there were very few present: only one or two monks, as I recall, and an old woman. I arrived near the end of the service, shortly before the moment when he emerged to give communion.

No one came forward to receive the sacrament, but he remained standing with the chalice in his hand; and with his head on one side in his characteristic way, he stared fixedly and even fiercely in my direction (he had never seen me before). Only when I shook my head did he return to the sanctuary with the chalice.

After the conclusion of the Liturgy there was a service of intercession (paraklesis, molieben) in honor of the Saint whose day it was; and at the close the Archbishop anointed those present with oil from the lamp before the Saint’s icon. I stayed where I was, not knowing if as a non-Orthodox it was appropriate for me to receive anointing. But this time he would accept no refusal. He beckoned firmly, and so I came forward and was anointed. Then I left the chapel, too shy to stay behind and speak with him (but we did meet and talk on future occasions).

St John’s action at the moment of communion puzzled me. I knew that, according to the practice of the Russian Church in Exile, anyone intending to receive communion is required first to go to confession. Surely, then, the Archbishop would have been warned if there were going to be any communicants. In any case, a prospective communicant — at least in a Russian church — would not have arrived so late during the service. The Archbishop was gifted with the power to read the secrets of the human heart; had he perhaps some intimation that I was on the threshold of Orthodoxy, and was this his way of telling me not to delay any longer?

Whatever the truth of the matter, my experience at Versailles strengthened my feeling that the moment had come for action. If Orthodoxy is the one true Church, and if the Church is a communion in the sacraments, then I needed above all else to become an Orthodox communicant.

Leave a Reply