by Clifton D. Healy

My Discoveries in the Orthodox Church: Introduction

My Discoveries in the Orthodox Church: Introduction

I grew up in and trained for ministry among the Restoration Movement churches. Toward the end of that training, while still at college, I began to investigate the Anglican tradition. And though for a time these two faith traditions overlapped, still the pathways are fairly clear.

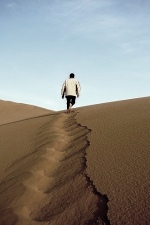

The road markers for my journey to Antioch, my inquiry into the Orthodox Church, however, are much more muddled, scattered here and there along previous roadways, seen now as portents of things to come, but known then as only so much new experience, as simple signposts which I was then unable to read.

The relating of my investigations into Orthodoxy, then, runs scattershot at first through the stages of my experience in the Stone-Campbell/Restoration Movement churches just prior to becoming acquainted with Anglicanism, then through my initial searching in the Anglican tradition, and finally to the culmination of my experience in that tradition as I turned away from the Episcopal Church to finally look with focused attention at the Orthodox Church.

My experience of Orthodoxy can therefore be roughly charted along five time markers: the years prior to the summer of 2000, the months from June 2000 to January 2002, from June 2002 to September 2003 (the “gap” from January to June 2002 will be addressed in due course), from September 2003 to the Sunday of Orthodoxy and our entry into the Cathecumenate, the Catechumenate from the Sunday of Orthodoxy to Pentecost, and our entry into the Church on Pentecost.

1. Encounters with Orthodoxy prior to June 2000

As has been told elsewhere, by the summer of 2000 I had looked outside my own heritage churches to find that longed-for connection to the historic Church and had made my way to Anglicanism in the belief that I had found it there.

But the search had antecedents that predated my Anglican investigations. The first event in which I can recall this longing began to manifest itself with the purchase, in January 1987 between semesters of my freshman at Ozark Christian College, at the college bookstore of the Lightfoot and Harmer Greek and English single volume edition of The Apostolic Fathers. Here was my first attempt to find out what the early Church taught and believed.

A seed had been planted as I spent the next semester reading through the Apostolic Fathers. I had no real understanding of what I was reading, but it both satisfied and intensified my longing for a connection to the New Testament Church.

The next event occurred about four years later. In the spring of 1991, just prior to my graduation from college, I prepared for a conditional baptism. I was seeking some certainty and authenticity about my baptism at age seven, especially in light of the fact that my life as an adolescent was godless and immoral. The preparation brought to my attention, for the first time, the Jesus Prayer, and aside from the Lord’s Prayer, was my first experience with an ancient prayer of the Church. All my experience to this point had been oriented solely around extemporaneous praying.

In the summer of that year (1991) I read the first edition of Peter Gilquist’s Becoming Orthodox. This was my first real and formal introduction to the Orthodox Church. During this time I had been investigating Anglicanism (and later that autumn, I would seriously consider, if only briefly, the Roman Catholic Church), so I cannot say how or why I chose to buy the book.

Perhaps it was knowing that one of the persons noted in the book, now Fr. Gregory Rogers, was an alumnus of Lincoln Christian Seminary, where I later earned my M. A. in contemporary theology and philosophy. In any case, though it did allay my concerns related to Mary and the Tradition, it still seemed to me that Orthodoxy was too foreign, too ethnic for me. Which is ironic, considering that Gilquist’s book recounts the journey of a couple of thousand of evangelicals to Orthodoxy.

But there you have it. To me Orthodoxy was foreign.

A few months later, in the autumn, I read The Way of a Pilgrim and was reintroduced to the Jesus Prayer. But by this time I was more intent on assimilating ancient Christian spiritual disciplines in my life than in understanding Orthodoxy any further.

After that, my encounters with Orthodoxy were infrequent, though they continued to be bookish. I read Timothy Ware’s The Orthodoxy Church in the autumn of 1992 and his The Orthodoxy Way in the summer of 1996. Daniel Clendenin’s two books, from an evangelical Protestant perspective, helped to further clarify some points of concern in the spring of 1995.

But although in the spring of 1993 I did purchase a few Orthodox prayer books and a small laminated icon, I was still very much the intellectual tourist. And these items were being used to deepen my exploration and experience of, ironically enough, Anglicanism.

I made no real use of these things, at least not on their own terms. I merely knew about them.

2. Orthodox Encounters June 2000 through January 2002

From my last couple of years Ozark Christian College (1990-1991) till my decision to leave the priestly vocation discernment process in ECUSA in January 2002, I was moving into, then back out of, Anglicanism. Although in those years

I acquired icons and prayer ropes, there was no real assimilation of Orthodox worship and prayer, and only infrequent reading of Orthodox books. Indeed, my first visit to the Divine Liturgy took place in October 1998, at St. Mary’s in Omaha, Nebraska, during a three-week stay while I was training with a company for which I had just been hired. I had already been an Episcopalian for two years, and so I went mostly out of curiosity. It was a beautiful and moving experience, but it still felt too foreign to me, especially now with my developing Anglo-Catholic ethos. I would not visit another Divine Liturgy until July 2000.

In the spring of 2000, I had begun attending an Episcopal seminary as part of a discernment process for a priestly vocation in the Episcopal Church. After a scant three months, I was shocked and angered. I had seen the Gospel mocked, godly Christian men and women ridiculed, and the Scriptures dismissed with a wave of the hand–all because these things spoke against, or these persons by their lives revealed the futility of, the majority’s political agenda.

I very nearly decided not to go back once the term ended. And in time I would come to the conclusion that the forms and structures of the national Episcopal Church, as well as a plurality of dioceses, had been so corrupted by heresy and the grab for power, had been so wed to a singular political agenda, that no reform was forthcoming. I would risk the spiritual well-being of my family to have stayed. And in my mind I was called first to be a priest in my family, not to the institution that is the Episcopal Church.

But as it turned out, at the end of that first term, a serendipitous receipt of a postcard from Frank Schaeffer’s Regina Orthodox Press, advertising a videotape of an interview on the program “Calvin Forum” (hosted by Bob Meyering) with Frank Schaeffer, son of the famous Presbyterian theologian Francis Schaeffer, led to what became a six-year inquiry into Orthodoxy.

I purchased and watched the video. I recalled the Gilquist book I had read some nine years ago. And that old longing for the historic Church and its real presence was reawakened after the disillusionment I had recently experienced.

After watching the video, a chain of connections unrolled in the space of about a month which would put in place two very important factors: a disciplined study of Orthodoxy and a parish in which to experience the Orthodox faith and life. It was that latter reality that has made all the difference.

Having watched the Schaeffer video, I did some searching and found his book Dancing Alone at a local library, and checked it out and read it. More research led to two of Frederica Mathewes-Green’s books, Facing East and At the Corner of East and Now. A few weeks later, on a trip home to Wichita, Kansas, over the Fourth of July, I visited my favorite bookstore, Eighth Day Books, and purchased the revised edition of Peter Gilquist’s Becoming Orthodox as well as the book he edited, Coming Home of personal accounts of how men from various Protestant backgrounds had become Orthodox priests. There would be many more like this.

This initial interest and burst of reading generated many sessions of surfing the web, looking for information on the Orthodox Church. From the books that I’d read, as well as many web links, I found the website of the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of America, and through it’s parish directory search got the information for All Saints Orthodox Church. I contacted the parish pastor, Archpriest Patrick Reardon, and was warmly invited to come worship at the Divine Liturgy.

At this point I had almost decided not to return to seminary, and, in fact, to leave the Episcopal Church altogether. I had discovered Orthodoxy, and in the space of about a month and a half had been so drawn to what I had learned of the Orthodox Church that I was now wondering if I shouldn’t continue my Christian pilgrimage, leave Canterbury, as it were, and continue on to Antioch. In fact, I made a list of resolutions in which I began to attempt to appropriate the life of the faith of the Ancient Church. As far as I could then tell, it wasn’t Anglicanism that had that life, but Orthodoxy. And so the last resolution was that if I ever left ECUSA, I would become Orthodox.

Of course, the question is properly raised: How could I so suddenly, having just started at seminary to discern a vocation to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church–and having uprooted my family and limited our employment and educational choices–even think of abandoning the Episcopal Church?

Hadn’t I spent about five years investigating Anglicanism before my confirmation? Hadn’t I spent four years trying to further assimilate Anglo-Catholic traditions into my faith practice? Hadn’t Anna and I worked hard to come to some compromise about the Episcopal Church, my confirmation being something she had been opposed to? Was I ready to throw all that away?

Not yet. My journal entries at the time were full of ambivalence. My initial picture of the Episcopal Church had been fueled and fed by Robert Webber’s, Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail. But the picture that book had presented was now a decade and more out of date. In fact, one may well question whether Webber’s optimism of the place of evangelicals in ECUSA was either unfounded or misplaced. I now had a more realistic understanding of where the national church was and where it was headed. My questions now had less to do with whether or not I was called to the priesthood, but whether, if so called, I could serve without compromising my faith or putting my family at spiritual risk. Still, my parish priest was a significant influence through his friendship and pastoral mentoring.

And my bishop was an example of godly leadership against the tide of rejection of biblical and traditional norms of faith and life.

And, given my experience of judging a church on the basis of reading alone, I was much less sanguine that reading a handful of books and surfing the internet was a solid basis for making a change that would involve scrapping the hard work and planning that had brought us to Chicago in the first place.

Still and all, Orthodoxy beckoned, so on 23 July 2000, I worshipped for the second time at an Orthodox Church. I went to the Divine Liturgy at All Saints.

I was absolutely blown away. Since Fr. Patrick was out of town that weekend, a deacon from another parish served the typika liturgy. The service was still foreign to me. And the differences in pious practices was evident. I genuflected whereas everyone else bowed. I crossed myself backwards (or was it the parishioners who were crossing themselves the “wrong” way?).

I bowed at the Gloria Patri, whereas everyone else crossed themselves (though many also bowed). The singing was a capella, which would have called to mind some worship experiences in some of my heritage churches, except that the hymns sung were all unfamiliar to me. I recognized, of course, the Pater Noster, the Sursum Corda, the Nicene Creed (sans filioque) and a few other pieces of the Liturgy, but the rest of it was a jumble, despite the copies of the Liturgy (with explanation) in the pew.

But what wasn’t foreign to me was the content of what I was hearing. At the seminary I had already been subjected to liturgies that eliminated the Fatherhood of God, that struck out the human maleness of Jesus, that replaced robust Trinitarianism with bland Sabellianist notions of a monochrome God, that nixed confession of my personal acts of sin, and that offered a running critique of the Tradition as patriarchal, oppressive, and, well, outdated.

Here, however, all of that which had been denied me at the seminary liturgies was present in all its fullness. Here the Trinity was confessed in full, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Here Jesus’ two natures, united in one Person, was confessed and expressly linked to the cause of our salvation. Here God was Father, fully and completely. Here our sins were confessed in a variety of ways. Here the Tradition was alive, fully vibrant, and salvific.

If I could have, I would have become Orthodox right then.

But, in God’s wisdom, he has blessed me with a wife that frequently intervenes to bring me to a more level-headed and realistic path of action. Some time after worshipping at All Saints, I was still enthusiastic about the Orthodox Church, and in a conversation my wife and I were having, that intensity shone through. But she bluntly and firmly drew the conversation to a close by saying,

“We’re not changing churches again.”

That accomplished God’s purpose, which was to give me pause and to deeply consider the claims of Orthodoxy. It is not a coincidence, then, that I did not return to worship at All Saints for some six months. Nor is it a coincidence that I decided to return, after all, to seminary. I determined that I should try to enter more deeply into the Anglo-Catholic traditions I had known as a way of surviving the seminary experience.

But I did not stop my pursuit of and inquiry into the Orthodox Church.

After a couple of months actively engaging with Orthodoxy, I returned to my Anglican ethos and tried to find within it resources to overcome what I took to be its weaknesses and failure. I sought this mainly in traditional liturgical forms and pieties. I tried to use the 1928 prayer book and the Anglican Service Book. I read some of the Carolinian divines. But I found that this retreat into the Anglican past, good and holy though it was, did little more than emphasize that the Episcopal Church was, in my view, going further and further down a road I not only did not want to go, but one I was certain would end in destruction.

In January 2001 I began more fully to realize these things, so I took a very conscious step back toward Orthodoxy by purchasing an Orthodox prayer book and a translation of the Septuagint psalter. These soon became my sole means of personal prayer. I gave up the Anglican prayer book for good. Also that month, I again visited All Saints Orthodox Church.

During the next few months, my life was incarnate ambivalence. I had one foot pointing to the world of Orthodoxy, and one toward the Episcopal Church. I had grown increasingly unclear as to my diocesan status as an aspirant, and was coming to the conclusion that my search for holy orders was effectively over. I talked with my parish priest and he contacted the bishop. The three of us arranged a lunch meeting in May. That meeting even more firmly solidified the backing of my bishop, especially given we were of like mind on many current matters in ECUSA.

Still, despite being in limbo for some months, yet now having a clear green light, I was disappointed. Had the bishop cut me loose, my decision would have been clear and relatively easy. Now I was forced to do ever more thinking. ECUSA or Orthodoxy?

For Mother’s Day, May 2001, and again in June, my wife graciously accompanied me to two Orthodox Liturgies. The first was at Sts Peter and Paul Orthodox Church in Glenview, the second was her first visit to All Saints. She was curious and asked some questions, but ultimately unimpressed. Eventually, she would become deeply resistant to our being received into the Orthodox Church.

In the autumn of that year, I began my doctoral program in philosophy at Loyola University in Chicago. During that semester my own sense of vocation and the status of the Episcopal Church became clear to me. On Christmas Eve, I prayed and wrote a list of issues I had with the Episcopal Church. After two weeks of reflection and further prayer, I decided to stop the process of discernment to a vocation to the priesthood. On the Feast of Epiphany 2002, I emailed my priest, and later contacted the bishop and my parish discernment committee. When I told Anna, there was visible and verbal relief. She summed it up in her response to me:

“Good.”

A week later I returned again to All Saints. I had lunch with Fr. Patrick and Khouria Denise. He answered a lot of my questions and gave me a prayer rule. I continued to study further about Orthodoxy. But the toll of the previous year and a half worked itself out in me. I soon went into a state of numbness and apathy. I stopped attending worship altogether. I rarely prayed. I felt stuck between.

I had given up on the Episcopal Church and Anglicanism.

There was no evangelical church that appealed to me. And with Anna’s growing resistance to a new church journey, let alone the strange world of Orthodoxy. So for six months, from January to June 2002, I was nowhere in terms of a church home. Orthodoxy still beckoned, and I knew my heart lay there. But I was out in the wilderness. Something eventually would have to give way.

And as you may suppose, it started with repentance.

3. Orthodox Encounters June 2002 to September 2003

On 9 June 2002, I returned to All Saints Orthodox Church after a six-month absence.

The week before, through a serendipitous reference in my reading to the passage in Ephesians 5 on the relations of husbands and wives, I contemplated my responsibilities as a husband. According to the Scriptures, and my own conscience, I came up far short. Especially in the critical role of my obligations of leadership in my home in matters of faith.

As I’ve described, my first reactions to the new realities confronting me in the Episcopal Church and in seminary, as the 90s drew to a close and the new century and millennium began, were largely ones of anger and repulsion.

I was angry that the church I thought I had joined had, in effect, ceased to exist more than two and a half decades before. I was angry that I had not seen the truth when I was being confirmed, and angry at those changes which had manifested themselves after my confirmation. I was also repulsed by the approval of immoral behavior and the ever-growing influence of heresy in the communications of the church, heresy which was never seriously or prominently addressed, let alone disciplined. No bishops or priests were brought up on presentments for preaching that which contradicted the explicit Faith of the historic Church.

It seemed it was more important to uphold institutional unity, to hold on to property and endowments, to earn the esteem and approval of those outside the Church, than it was to stand firm in the Faith once for all delivered to the saints.

Clearly, then, my turn to Orthodoxy at first was more about greener pastures than about embracing Orthodoxy for what it was. But from the time I acquired an Orthodox prayerbook and the Septuagint psalter in January 2001, I began to relate to Orthodoxy on a deeper, more serious level. My exploration of the life and doctrine of the Church began to lay a solid foundation for change, so that by the time June 2002 came ‘round, I was in a state in which I no longer evaluated the Orthodox Church on my terms and preferences. I was now prepared to listen to the Orthodox Church and, importantly, to begin to allow Orthodoxy to evaluate me.

It was fitting, then, that the Sunday of my return, 9 June, was the Sunday of the Blind Man (the Gospel reading being John 9:1-38), and that Epistle reading was Acts 16:16-34, and the conversion of the Philippian jailer.

This was my first of a handful of “St. Anthony moments.” As you remember, St. Anthony had gone to worship, heard the Gospel text to sell all he had and give it to the poor, and soon went into the desert to pray and wage spiritual warfare. Though certainly with more humble implications, nonetheless, the significance of these passages were not lost on me. Clearly I was blind, and in need of the illumination of God’s Spirit. But I took the promise of St. Paul to the Philippian jailer as my own:

“Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved, and thy house.”

As completely unrealizable as it seemed, I began to hope that one day I and my entire household would be Orthodox.

For I had come to believe, though I did not yet understand, that the Orthodox Church is the Church of the New Testament. If this were true, then not only by virtue of my growing up in the Stone-Campbell/Restoration Movement churches, but also on its own terms, I needed to lead my family into that Church, and to do so by way of example.

Immediately, that implication, and my new resolve to accomplish it, faced a strong and serious challenge: my wife was completely opposed to any such move. Although she refrained from any critical remarks about my worshipping at the Orthodox Church for nearly a month, by the first of July 2002 Anna vigorously voiced her frustration and opposition. My continuing to worship at a Church she could not see fit to worship at was just like if I were taking a knife right through the midst of our family and dividing it in half. I had two weeks to decide what I was to do: continue to go to the Orthodox Church and wreak havoc on our home; or find a parish where we both could worship together as a family.

Needless to say, I was sat back hard on my heels. Anna had clearly, honestly, and tearfully expressed her deep felt belief that my worshipping in an Orthodox Church was spiritually divisive, that it deeply wounded her that I would seem so callously to set aside her particular worship and church life needs, and that I should seriously consider what it was I was doing.

These deep feelings and hurt had been growing in Anna for some time. She could hardly be blamed. I had been adamant in my desire to be confirmed in the Episcopal Church some six years before. She had been against it, citing all the reasons of heresy and immorality for which I would eventually leave the Episcopal Church (though of course neither of us could have foreseen some of the particulars).

I at that time had defended my stance, saying that God would bless my decision to be confirmed, that I was doing it for our family, and so forth. Though we reconciled enough that she gave her blessing four years later for me to seek ordination, she had sacrificed potential career opportunities in the narrowing of her employment choices so that I could go to seminary. Now here I was, having left the church I was so certain was going to be good for our family, having left the ordination process I was so certain God had called me to explore, and now I wanted to jump the fence and explore yet another greener ecclesiastical pasture.

No, clearly Anna had strong and legitimate reasons to be upset and resistant to my journey into Orthodoxy.

At first, her reaction both scared and angered me. I was concerned that perhaps this issue would test our marriage beyond the breaking point, and that I would do some boneheaded thing to put the finishing touches on nearly a decade of matrimony. And I was angry that my intent to investigate Orthodoxy as a specific fulfillment of the Holy Spirit’s convicting me of my failure to be the husband I was called by God to be was being criticized in a way contrary to my intentions.

But I also had a sense that the either/or condition with which I had been presented was a false choice because it was no real choice. It pretty much came down to: choose Orthodoxy and my lifelong pursuit of the New Testament Church or choose my wife and our marriage. But after two weeks of prayerful reflection I finally decided to offer a different set of choices: we would together worship at a church with which she was comfortable, and I would from time to time (say once or twice a month) go to the Orthodox Church.

I knew that neither of us considered this compromise as ideal, still it served to reduce the tension and provide some breathing space. We ended up going to a Disciples of Christ congregation that had the sort of contemporary style of worship my wife enjoyed and felt best enabled her to worship in spirit and truth. Though I wanted her also to go to All Saints with me, she chose not to and so on those Sundays I went to Divine Liturgy, she stayed home.

Such a stopgap state of affairs could not go on indefinitely. I knew that if I were to have any hope of seeing the fulfillment of the promise I sensed I had been given, I would have to found my convictions about Orthodoxy on something other than my experience and purported preferences, on something other than reliance on “authorities” in books, and on something other than my reaction to the Episcopal Church.

It was my own heritage that pointed toward the beginning of a way forward. I would go back to the New Testament to find there the foundation of my transfigured belief and would support that biblical interpretation by the testimony of the early Christian witnesses, the Apostolic Fathers and their successors.

In July 2002, I began six months of reading and study, reflection and writing on the key questions to which I needed answers. Answers that would address not merely intellectual matters, but the issues of the life of faith. This project, though it did not begin quite so large as it ended, was much less about an academic study of, say, whether or not the Church had always believed that the elements of bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist, but rather, if this is indeed the case, what am I then to do about it?

So, what began as an anticipated handful of questions I might answer in a paper grew to eight related essays (three on the nature of the Church alone), totaling some ninety-two typescript pages and more than thirty thousand nine hundred words. I started the first essay on 31 July, and began the last essay on Christmas Eve (finishing it the day after New Year’s Day).

The first two essays were intended to clear the ground and note the boundaries. In the first I noted that the competing and contradictory beliefs of the various Protestant bodies pointed out both the weaknesses of the Protestant paradigm and that the Truth had to be there amidst all the antagonistic notions. In the second essay I established the Protestant problem: that the New Testament clearly points to the visible unity of the Church, and that Protestantism has not only created more than twenty thousand schisms, but continues to add to them each week.

From there I could only resort to one sure thing: the Tradition of the Church, so the third essay highlighted how it is that the Tradition is essential to Christian belief. It is that Tradition which reveals both the antiquity of the office of the Bishop, but also underscores the New Testament teaching that the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper become the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ in the Church’s Eucharist. The last three essays deal with the reality of the unity of the Church, that the Church is both the Body of Christ and by that, then, is the locus of our salvation, and finally that the criteria of the true Church would have to be both historical and doctrinal continuity with the Church of the New Testament.

But the months from July to the Christmas season were not merely about study, however, “real life” that study was. In mid-July, Anna and I worshipped for the first time at Northside Christian Church.

This was a Disciples of Christ congregation just about a mile from our home. The Disciples churches had the same historical pedigree of the churches of which Anna and I had been members (and had served as ministers early on in our marriage), so there was some familiar ground. Plus Northside had one of the most well-done contemporary praise-band worship services I’d ever seen done, which was a key factor for my wife.

Anna and I worshipped there a few times a month for a couple of months. Both of us met with the husband-wife ministry team, and I myself met with the pastor a couple of times. But though one would think we had found our “compromise parish,” early on even Anna had misgivings. In our first meeting with the pastors over lunch, we asked some direct questions about doctrine, morality and church discipline. We did not receive direct answers. And the answers that were finally forthcoming seemed to us to display a willingness to dilute the tougher teachings of the Church for the sake of something like “church growth.”

By the first of October, the congregation had relocated to a rented movie theater in Bucktown and changed its name. We went once after the move, but the atmosphere felt to us less like worship and more like the sort of spectating one does in a theater, complete with snacks, soda and cupholders in the arms of the theater seats. We did not return. I took the move as a sign from God that this was not what he wanted for us.

The first Sunday in October, as it would turn out, was my last visit to the Divine Liturgy at All Saints until December. The following weekend I went to the Benedictine monastery of St. Gregory’s Abbey, in Three Rivers, Michigan. It was to be, in a most significant way, an unlooked-for transformation.

I arrived a few minutes late for dinner at St. Gregory’s Abbey on that October Friday, the eleventh. Arriving late is not a good thing at a monastery, but being Benedictines they were unfailingly gracious and served me a heaping plate of food nonetheless. St. Gregory’s observes the canonical offices of Matins (4:00 am), Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. So after a brief opportunity to unload the car and unpack, it was time to head to the abbey church for Compline. I wandered around a bit in the monastery library, then headed back to the guest house, did some journaling and headed to bed.

The weekend was the wonderful Benedictine dance between work, study and prayer, though as a guest I was left to my own devices during the community work hours. I did some reading and journaling between offices. I ate with the brothers and other guests. I rested.

I came to the abbey with no real agenda, other than knowing I needed to go there. I’d been to the abbey on a couple of other occasions (though the last visit had been four years before), each visit of which was an intense time of prayerful consideration of a vocation and the seeking of some confirmation of its certainty. On the drive over to the abbey this time, however, I simply told God I had no agenda other than the one he had for me.

If “nothing happened” that would be fine. I would just trust in him.

But as it turned out, one of the books I’d checked out was a service of the Akathist Hymn to the Theotokos. I had not developed any sort of “devotion to the Virgin,” and, indeed, other than the prescribed instances in the Divine Liturgy and the service of Morning Prayers, I’d never really sought her intercessions. But I remembered that in the West, Saturdays were uniquely devoted to the Blessed Virgin, so, on Saturday afternoon, I developed the idea that in the meditation time after Compline, I would pray the Akathist hymn in one of the chapels running along the side of the monastery church.

It was an experience of prayer that was more about the distraction of standing and attending to only about ten percent of the words than about anything else. From the paradigm of spiritual experience I’d gained from my heritage churches, the prayer was a “non-experience.” No feelings of piety. No mystical flights of fancy. But, strangely enough, it was a prayer about which I suddenly wanted to develop a routine of praying.

The weekend ended Sunday after lunch. I headed back to the abbey church to spend a few moments in prayer in one of the side chapels. I prayed, as I’d done from several months, for the unity of our family and home in spiritual matters. I began to pray for Anna.

Then, quite unexpectedly, I was overcome with sobbing. I had a glimpse of my own unworthiness before God, of my sinfulness. In the prayers that came forth, I asked the intercessions of the Theotokos with regard to our family and the Orthodox Church.

As quickly as it came on me, the crying left. I prayed a bit longer and then left. Soon I headed home.

Through the next month at home life was just as it had always been. I was doing more serious reading in Orthodoxy, particularly Panayiotis Nellas’ Deification in Christ. In my daily prayers, however, I soon took on the practice of asking the intercessions of the Theotokos for me and my household. I began specifically to ask the prayers of our Lady for my wife.

On Monday, 2 December, my wife went to the doctor. She’d been feeling ill for a week and just wasn’t shaking it. I touched base briefly with Anna prior to my evening class. Then, class over, I headed home in a Chicago snowfall. But oddly enough, for me, my thoughts were not on class or some theological idea, which was usually the case. I often reflected on such things on the walk home. No, this night, my thoughts were daydreams about the future, and the children we hoped to have and raise.

Which was interesting, because I’m not, by any stretch of the imagination, an “intuitive” person. But when I walked in the door, Anna had news for me.

Anna was pregnant. This was joyous news. Though at first, the transition in our lives from ten years of family as couple to family as mommy, daddy and child, was emotionally tough, especially for Anna. She was smack-dab in the midst of rapid career development, and looking forward to continuing her education either in writing or in studying children’s literature. Now she was a momma. For my part, all I could see at first was the economic need to suspend, if not cancel altogether, the doctoral program I was so close to finishing.

As it turned out, those first misgivings, natural as they were, soon gave way to undiluted joy, acceptance and anticipation. Sofie took us out of ourselves and gave us a greater love to share.

I got the news on Monday, 2 December. The next Sunday I was back at All Saints to offer my thanksgiving to God, and to seek his strength. It was clear to me, almost from the beginning, that Sofie’s advent was in part, an answer to the prayers of the Theotokos for us which I’d been praying now for a couple of months. At first I had to take this somewhat on faith, though the conviction was strong. But as the months have unfolded since then, events have seemed to bear this out.

By the end of the month, I was finalizing the several essays I’d been working on about Orthodoxy. I also read Metropolitan John Zizioulas’ Being as Communion. This, in conjunction with Nellas’ Deification in Christ, served to further fundamentally shape my understanding of the Church, the Trinity and salvation. These books drove me back to the New Testament to confirm and reason out what it was they were saying. I began to understand that the individualistic faith I’d been reared with and trained in as an adult was antithetical to the prima facie text of the New Testament. If I gained nothing else, I learned that almost always, when Paul uses “you” in his letters to the churches, it is collective. We are saved together. And that has far-reaching implications.

While all this was going on, about the middle of the month, I had my second “St. Anthony moment.” That is to say, while worshipping and hearing the lections for the day, the word of God hit me right between the eyes. In June I was the blind man whose sight had been restored and the jailer who had received the promise of the salvation of his entire household. This time, God was much more direct. The Gospel reading was from Luke 14:16-24, the parable of the wedding supper and those who refuse to come. One reason given by one of the invitees: I’ve just gotten married. I was hardly a newlywed, at (then) nine years of marriage. But I had to ask myself: was my marriage more important to me than the truth of God’s Church?

As I hope has been evident, I had, for some seven months by this time, done the best I could to balance both my pursuit of the truth about the Orthodox Church and the needs and demands of my marriage. In an ideal world, these would not have conflicted. But as has been told, I am not an ideal husband, even if this were an ideal world. By the same token, I had to legitimately ask myself, was I more concerned about avoiding Anna’s anger or more concerned about living the truth in love, even when this truth did not coincide with Anna’s beliefs?

One thing of which I was certain: if I were ever to become Orthodox, I wanted to do it as a family. And I was growing in my certainty that I was not alone in this desire. It seemed that God and the saints interceding for us wanted that as well.

Advent that year was extremely meaningful. I came to sense more deeply what it meant for the Lord to take on Mary’s humanity, to become a man and live as one of us. I was joyous at the thought of becoming a new father. Anna was much more ambivalent, and this, augmented by the newly surging hormones of pregnancy, made for an emotional time as she worked through her anxieties and embraced her joys.

In light of my own struggle to balance my Orthodox inquiries and Anna’s needs, I did not return to All Saints till the following February. I have, to this point, lingered quite a bit over the half-year period from June to December 2002.

This has mainly been because this was perhaps the most important several months yet in my inquiry about Orthodoxy. During this time I had settled important questions in my mind regarding the biblical nature of the place of Tradition, of bishops, of the transformation of the Eucharistic elements, and of the implications in terms of salvation and sanctification, of visible unity and historic continuity, resulting from the Church’s being the Body of Christ. I had “discovered” the reality and aid of the intercessions of the saints on our behalf, particularly of the Theotokos. And I had become a father. Mind, worship, heart and family had been radically re-formed in just over two hundred days.

The living into that reality, however, even now has only barely just begun.

© 2004, 2007 Clifton D. Healy

Leave a Reply