by Fr. Andrew Phillips

“They were old men with no scholarship. They told me of their thoughts: the things they said within themselves as they sailed with the stars and with the wild waters about and beneath them. I have never heard fairer things than fell from the lips of those unlettered men. It was the poetry of the grace of God.”

From a letter concerning the fishermen of Leigh in Essex of ? 1900

If we take a human lifetime as the Biblical threescore years and ten, only fourteen lifetimes ago the English Church was an integral part of the Orthodox family, belonging to the Universal Church of Christ. For nearly five centuries the English were in communion with the rest of Christendom. There were close contacts with Eastern Christendom. One of England’s sainted Archbishops, Theodore of Tarsus, was a Greek; Greek monks and a bishop lived in England at the end of the 10th century, and Gytha, the daughter of the Old English King, Harold II, married in Kiev. It is clear that during such a long period, a half-millennium, the Christian faith impregnated the way of life of the people and the Old English monarchy. It is clear that traces of the Faith of the first five centuries of English Christianity, a Faith that was Orthodox though not Byzantine, must have remained after the 11th century.

Of course it is true that England suffered the 11th century Papal reform of the Western Churches, and indeed this was particularly brutal in the British Isles, following, as it did, the papally-sponsored Norman Invasion of 1066. It is also true that England suffered another blow in the Reformation instigated by such tyrants as Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and the iconoclast Cromwell. All this represented a loss of spiritual culture, the denial of the saints, the deformation of ecclesial tradition, and the resulting loss of ‘texture’ or spiritual quality of English life. This is not to say, however, that the falling away or apostasy of England and the other Western nations from Orthodox Christian Tradition occurred everywhere at the same pace.

Since the 11th century, England has experienced high and low points in her spiritual and cultural life. The high points represent a slowing down in the process of apostasy, the low points a speeding up. The high points have been spiritual and cultural peaks, when the English nation, her perception sharpened through prayer, fasting, repentance and love of the Gospel, has been guided by Christ, the Mother of God, her national saints and her Guardian Angel, and so glimpsed her soul. Conversely, the low points have been those moments when the English nation abandoned her spiritual and cultural traditions and moved away from her divine calling and destiny. However we may judge the past, and some high points and low points seem to be apparent at once, it seems clear that, as with other Western peoples, today is a period when the apostasy is speeding up and we are heading more and more rapidly for the Apocalypse.

But it must be said that the very nature of the cause of the separation of the West from the Orthodox Faith, the filioque, implies that the process of the Western apostasy is gradual. The practical consequences of the filioque have only slowly filtered down into the life of the people, only slowly distorted the forms of popular piety. The Orthodox Christian heritage of the first five centuries of the English nation has survived in fragments. These fragments or vestiges are to be found particularly among country folk in the stock of accepted folk wisdom, in folk memory and fable, proverbial knowledge, ecclesial sense and the traditional practices of simple folk. What is traditional outwits the changing fashions of religious decadence and rationalist speculation, which were and are inherent in the filioque and its consequences.

The Christian Faith, which is made incarnate in the Christian way of life, can only be uprooted when the urban culture of ‘reason’ penetrates into the midst of those living in the rural, traditional, popular culture of the simple-hearted. In Western countries this only happened to any great extent in the last century. And here and there one may still meet individuals who have resisted the modernist rationalism of the towns until our own times.

One is aware of this in small villages in England, where perhaps survive a Saxon church or foundation, the Hall, and clustered around them, the inn and black and white thatched cottages. In my own experience, I know for example of old people who through family tradition still regard the Julian calendar as the only true calendar. (In England the Julian calendar was changed for the Gregorian in 1752, when 2 September was followed by 14 September which caused rioting – not surprising when one considers for example that a month’s rent would have to be paid for only nineteen days). Indeed the Julian or old calendar was until recently known as ‘English style’ and the Gregorian or new calendar as ‘Roman style’. (See the Oxford English Dictionary). In old books one still finds the doggerel:

In seventeen hundred two and fifty, Our style was changed to Popery, But that it is liked we don’t agree.

In farming families of my acquaintance in East Anglia, “Old Christmas” was religiously kept right up to Hitler’s War. The same for “Old Michaelmas”. Similarly parish feasts, fetes or ‘wakes’ are still in some areas kept according to the “English style”. Such faithful people know from their grandparents’ grandparents that Easter in England is kept on the wrong date most years. Such people, outside the Orthodox Church, bring to shame the Orthodox New Calendarists who seem to have less sense of tradition than they.

I would like now to speak of those traditions which I have either seen myself or read of, which all go back to a time when the English world was still part of Undivided Christendom.

It would seem that those ancient traditions are particularly associated with the Nativity of Christ. The Birth of Christ was an invitation to the whole of the cosmos to celebrate. It was said that at the moment of the anniversary of the Nativity that all Creation stood still—rivers ceased to flow, birds stopped in their flight. After this moment bells rang, even from churches that had disappeared under the waves, as at Dunwich in Suffolk, or from St. Wilfrid’s Cathedral which long ago sank beneath the waves off Selsey in Sussex. And then dogs barked, birds sang, bees buzzed, cocks crowed. All Creation united in praise of the Creator become man. A child born on Christmas Day (or for that matter on any Sunday) would never be drowned, so it was said.

Men celebrated in other ways. Everything had to be prepared before Christmas Day. Any work done on the day itself would turn out badly. On Christmas Eve, it is still the custom to set up window-lights, that is to put candles in the windows, to guide the Mother of God and St. Joseph, for whom there was no room at the inn. Holly is used as a decoration in homes and churches; the green is to remind us of the evergreen, everlasting life brought to us in the Birth of Christ, the red (berries) remind us of the blood on Christ’s brow from the crown of thorns at the Crucifixion. Mistletoe is hung at home, but never at church. A tradition says that this was because mistletoe was formerly a tree used in making the Cross. Because of this shameful use, it was then reduced to a parasite.

The Christmas tree itself, according to German tradition, originates from the event when the 8th century Devonshire saint and Apostle of Germany, St. Boniface, cut down an oak used for pagan worship. The oak fell in the form of a cross and a fir tree sprang up from among the roots, as a token of new life, and thus the new life that we have in the Birth of Christ.

It is said that when Christ is born, the oxen and the cattle on farms kneel down in worship and, according to some, weep. When in 19th century England a learned scholar mocked this belief, affirming that he had never seen it, he was informed by farm-laborers that this was because the scholar had been watching on 25 December, and not on the true date according to the Julian calendar. We are told that on hearing this characteristically Orthodox response, he departed in his pride, none the wiser. To this day the Glastonbury thorn and thorns taken from its cuttings flower not on 25 December, but around the 7 January. Similarly at the real Christmas rosemary, the rose of Mary, would blossom. The ash is also associated with the Nativity, for ash-logs are said to have been used to warm the Mother of God at the birth of Christ.

The food associated with Christmas was also symbolic. Christmas pudding, for instance, traditionally has thirteen ingredients, one for Christ and one for each of the Apostles. The mince-pie, which has been round in shape since Cromwell (who tried to ban it), was originally oval. This was to remind us of the shape of the manger and also the tomb of Christ (as on icons of the Nativity). The exotic ingredients, formerly with meat and spices, each represented qualities which the Birth of Christ had introduced into the world. This ‘sacred’ food was to be eaten in silence, while reflecting on the meaning of Christ’s Birth. Today this has degenerated into simply pausing and making a wish before eating the first mince-pie. It was also said that every mince-pie eaten ensured a happy month in the coming year. Associated with this is the still existent custom of keeping a piece of Christmas cake all year.

Christmas carols were once far more various and also theologically far more profound, like the Little Russian ‘koliady’ or the Serbian folk-songs of Orthodox Tradition. Incidentally the Church year was formerly celebrated popularly by all sorts of carols for every feast; today Christmas carols are virtually all that remain, and these mainly in Victorian guise, though some of the melodies are ancient.

After Christmas, Childermas or the massacre of the Holy Innocents used to be, and I believe, still is, celebrated by special muffled peals of bells. Theologically, this feast is most significant, since it commemorates the sanctity of unbaptised but martyred children; perhaps in our churches the list of Holy Innocents should also include all those children who have been aborted from the beginning of the world. In general the English art of bell-ringing is quite unique and surely reflects some of the glory of our Orthodox heritage.

Candlemas, the Feast of the Meeting in the Temple, 2 February, 40 days after Christmas according to the Orthodox method of counting which counts inclusively, was once much celebrated. Today it is remembered only by weather sayings and the names “Candlemas bells”, ‘Christ’s flowers’, ‘Fair Maids of February’ or ‘Purification flowers’ for snowdrops.

The childhood of Christ was also celebrated by various customs. Thus the juniper tree was said to have special qualities, for it protected Christ during the Flight into Egypt. To this day it is said that hunted foxes and hares find shelter under it, as did Our Lord. Lavender is said to have obtained its sweet fragrance from the fact that the Mother of God hung Christ’s swaddling-clothes on it to dry.

In spite of Reformation iconoclasm, the Mother of God is still remembered in popular tradition in England. It was not for nothing that England was formerly known as “Our Lady’s Dowry”, the equivalent of the Russian title, “the House of the Mother of God”, which was given to Russia in the days before the Revolution. We are left today with the beautiful names of the Feasts; Lady Day for the Annunciation, Our Lady in Harvest for the Dormition and Our Lady in December for the Conception of the Mother of God. The ladybird is in fact “Our Lady’s bird’, and nearly a dozen flowers are named after the Mother of God, for example, Our Lady’s Smock (Cardamine pratensis), and the marigold is in fact ‘Mary’s Gold’. How appropriate it would be to use such flowers to decorate icons of the Mother of God on Her various feast-days. Indeed, one wonders if such a practice might not be the ultimate origin of the names themselves.

As far back as the eighth century the Venerable Bede made the Madonna Lily, also called the Mary Lily, the emblem of the Dormition of the Mother of God, the Virgin. Mary, likening the white petals to her spotless body and the golden antlers to her soul glowing with heavenly light. To this day the saying that a bride must wear something blue at her wedding goes back to the liturgical blue, worn for the Feasts of the Mother of God. If a bride wears something blue, she is in fact asking for the blessing of the Mother of God on her marriage. The terrible tragedy is that the reverence of old for the Mother of God has so degenerated in modern speech.

The real meaning of the swear-word “bloody” is “By Our Lady”: it is in fact therefore a blasphemy.

Again, despite Reformation iconoclasm the notion of “image’ (= icon) survived. In the East Saxon (Essex) dialect, people will say:

“He’s a bad image” or “What an image you are!”

They mean that the image of God (=icon) may either be seen in them, or else is being lost in them. As regards images or iconography as such, they survived only in the piety of the sampler with its biblical text or proverbial wisdom (“No pains, no gains”, “What cannot be cured, must be endured”). They were being sewn until the beginning of this century and sometimes later in families of my acquaintance.

As regards flower-names, many are connected with the Saviour or the saints. Rose-campion is called “Our Saviour’s flannel” on account of its soft, velvety leaves. Hypericum calycinum is commonly called “St. John’s wort” and also “Aaron’s beard”. Verbascum thapsus is generally known as “Aaron’s rod”. And the Campanula medium is usually called the “Canterbury Bell”. Ragwort is also called St. James’s wort and there is also of course the Michaelmas daisy, so named from the coincidence of the feast and its flowering. The cowslip is also called St. Peter’s wort. [Incidentally another name for the haddock is St. Peter’s fish, since he was said to have caught one (Matt. 17, 27), leaving marks on its back made by his finger and thumb.] The eider duck, similarly, is also called St Cuthbert’s duck.

A great many traditions were and are connected with the Lenten cycle and Easter. The Saturday before Lent began, was and is called “Egg Saturday”, for then people started to use up their eggs, having already given up meat. The proverb

“Marry in Lent, live to repent”,

reminds us of the Church’s prohibition of weddings during fasts.

“After every Christmas comes Lent”,

reminds us that the Church’s Year was set by a rhythm of feasts and fasts, and also induces in us a sense of sobriety. The daffodil is still sometimes called “the lenten lily”. A common, meatless dish was lenten pie. Lent was also the marble season. This was so until a few years ago. The marble season finished at noon on Good Friday. The marbles were symbols of the stone that was rolled away from the tomb at the Resurrection of Christ.

Palm Sunday was also called “Fig Sunday”, for on this day figs, the fruit of the palm, would be eaten in pies and puddings.

Donkeys were treated with special kindness on this day. Incidentally, the cross-shaped mark on the backs of donkeys is said to come from the fact that the Lord rode upon a donkey.

Holy Thursday was kept with great piety, just as Good Friday. Even in my childhood all shops were closed on Good Friday—except the baker’s for hot cross buns (see below). It was called “Good” from the old meaning of the word “good”, signifying holy or spiritual, as is still the case when we call the Bible “the Good Book”. The elder was a tree never used by carpenters because it was said to be the tree from which Judas hanged himself and was called “the Judas tree”. On the other hand if the aspen tree is popularly called “the shiver tree” it is because Christ was crucified on one. So to this day it shivers with shame and horror.

On the English borderlands the Skirrid was said to be a holy mountain and the great cleft in its side is said to have been made by the earthquake at Christ’s Crucifixion. Churches in the English Marches were often built on earth brought from it. It was also sprinkled on coffins within living memory as a token of the Resurrection. Another Good Friday custom in the south of England was skipping; the skipping rope was said to symbolize that with which Judas had hanged himself.

As at Christmas, Good Friday and Easter were marked by cosmic events. All Creation participated. Thus it is said that the hawthorn groans on Good Friday, because it was used to weave the crown of thorns. If the violet droops its head, it is because the shadow of the cross fell upon it at the Crucifixion. The robin has a red breast because he pulled thorns from Christ’s brow, thus staining himself with blood. The expression “touchwood” comes of course from the custom of touching the Cross (wood) to protect oneself from the Evil One. To this day hot cross buns are eaten in England. Traditionally they have a healing power and are still eaten in some parts in much the same way as Orthodox eat prosphora or blessed bread from the Vigil. A few years ago a Herefordshire baker was recorded as saying:

“Bakers are important men – the Birth of our Lord and his Death – we’re at them both. We make mince-pies for His Birthday and hot cross buns for His Deathday.”

Good Friday was also considered a day of blessing for certain activities. Thus if seeds are sown at noon on the day, flowers will come up double (a token of new life and resurrection). Also bread baked on Good Friday will keep fresh all the year. On the other hand it was said that any sewing done on this day would come undone.

Just as the Russians have eggs blessed at Easter, so in England “pace-eggs” (paschal eggs) were blessed in church before they were eaten. In some places the tradition of “pace-egg rolling” still continues – consisting of rolling paschal eggs down slopes in play. These eggs represented the stone that was rolled away from Christ’s Tomb. On Easter Sunday, often called “God’s Sunday’ or “Holy Sunday”, one always wore something new (the “Easter bonnet”), as a token of new life. After the Easter-service, Easter breakfast (i.e. the breaking of the fast; it took place at about midday) would be eaten.

Here the eggs (always dyed red and only red – the colour of blood) would be eaten with the main Easter dish, lamb – the finest Canterbury lamb. This was garnished with mint sauce, an allusion to the bitter suffering through which the Lamb of God, the Risen Son, had passed. (Lamb is the traditional Greek dish on this day.) There was a custom of getting up before sunrise to see the sun dance for joy at the Resurrection – a custom that existed in Russia too. Some said that a lamb could be seen silhouetted against the disc of the rising sun. Sceptics were told that if they had not seen the sun dance, it was because the Devil was so cunning that he always put a hill in the way to hide it. In some parts it was held that one had to look at the sun reflected in a pool, in order

“to see the sun dance and play in the water, and the angels who were at the Resurrection playing backwards and forwards before the sun”.

Much weather-lore also concerns Easter. Thus:

“Whatever the weather on Easter Day will also prevail at harvest”,

or,

“If the sun shines on Easter Day, it will also shine on Whitsunday”,

or again,

“If it rains on Easter Sunday, it will rain on every Sunday till Whitsunday”,

or even,

“A white Easter brings a green Christmas”.

The linking of one feast with another through the weather shows the popular liturgical sense and how it was interwoven with the working year. As for tree-lore, the yew was and is used to decorate churches at Easter, since the yew lives for a thousand years and more, and is thus a symbol of the Eternal One, Christ. Graveyards were also decked at this time of year: the departed were not forgotten. Even today many put flowers on graves at Easter.

In 1991 the Orthodox Church celebrates “Kyriopascha”, that is to say the conjunction of Easter and the Annunciation. An old proverb about this is:

“When Easter falls in Our Lady’s lap, then let England beware of a sad mishap”.

Let us hope that this will not be so.

Easter celebrations went on throughout Easter (Bright) Week and on to “Hocktide”, the Monday and Tuesday of the following week, which corresponds to the Russian “Radonitsa”. A custom still observed at Hocktide is that of “heaving”. Local people literally lift one another off the ground, singing “Jesus Christ is risen again”. This unusual custom is said to celebrate the resurrection of the departed, the rising from the ground of the saints. We should not forget that the word “Easter”, from “East”, itself refers to rising, although in the sense of the rising sap of the Spring and the rising of the sun.

Ascension Day was celebrated piously in former times. If it rained on the day, the rain-water would be carefully collected and drunk. It was said that by His Ascension, Christ hallowed the sky and so the rain-water on this day had healing powers. I know that there are those who keep this custom to this day. On the other hand clothes must not be washed on Ascension Day, otherwise the life of a member of the family will be washed away.

Whitsun (Pentecost) means literally “White Sunday” from the fact that many were baptized on this feast and thus dressed in white baptismal gowns, but perhaps also from the white light of the Holy Spirit. In Somerset, “God’s Land”, it was customary for women to wear white ribbons in their shoes, or at least carry a white flower, perhaps a daisy. It was a great feast and bells which were rung on this day were decorated with red ribbons to remind the faithful of the tongues of fire of the Holy Spirit. The main dish this day was veal, in other words, the Biblical “fatted calf”, with gooseberry pie. This became a problem with the calendar change in 1752 for gooseberries are not ripe for an early Whitsun. Indeed an old rhyme says:

“For gooseberry tart at Whitsuntide, trim old wood out ‘ere Christmastide”.

Although saints were less venerated after the Reformation and many customs have been forgotten, some saints have remained in popular tradition. There are a great many sayings connecting saints days with sowing seasons and the weather. By far the most well-known is that connected with St. Swithin:

St. Swithin’s Day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain;

St. Swithin’s Day if thou be fair

For forty days ’twill rain no mair (more).

Less well known is:

“Till St. Swithin’s Day be past, Apples be not fit to taste”.

Of a multitude of saws, which deserve an article in themselves, connected with agriculture we may mention:

“David and Chad, Sow peas, good or bad”. (Do not delay sowing peas after 1 and 2 March).

“On St. Barnabas Day (11 June) mow away, grass or none”, or

“Barnaby bright, Barnaby bright, The longest day and the shortest night”.

These rhymes witness to the missionary work of monks who taught peasant folk how to remember saints’ days. Other rhymes include:

“For Lavender, bushy, sweet and tall, tend upon the feast of Paul”,

“Dig in old thatch at Annunciation, ’twill triple the yield; what jubilation.”,

“Of taters you will have the most, Praise Father, Son and Holy Ghost, Plant Parsley fair on Lady Day, Away from Rhubarb and from Tare, Remember! – Say the Lord’s Prayer”,

“Plant Broad Beans on Candlemas Day, one for the Rook and one for the Crow, one for the Nick to rot away, And one with God’s blessing to grow”,

“To John the Baptist praise be due, the straw flower buds have just come through.”

The great problem with these sayings is that after the 1752 calendar change, most of them became untrue. For example St. Barnabas Day, referred to above, was the longest day and the shortest night, but after 1752, it fell simply on June 11. What we now call an Indian summer is still called St. Martin’s or St. Luke’s little summer. The exclamation “By George” was originally an appeal to the nation’s patron saint for help and intercession.

The sign of the cross is recalled in a degenerate form in crossing the fingers for luck and the schoolchild’s solemn promise, “cross my heart and hope to die”. I know of housewives who still make the sign of the cross over any bread, cake or pastry they bake to ensure that it turns out well. Incidentally they make the cross in the Orthodox fashion – it should not be forgotten that the Roman Catholic inversion only goes back two or three hundred years. Similarly I know of people who still place a poker crossways over a fire, thus making the sign of the cross, to ensure that the fire does not smoke. Until the nineteenth century crosses would often be carved on doorsteps, sills and lintels, to “keep out the Devil”. At weddings millers used to set the sails of their windmills in a position known as “the Miller’s Glory”, i.e. like a St. George’s Cross, not a St. Andrew’s Cross.

There are also birth and burial customs of great Christian significance. A child born at the “chimes hours” i.e. the hours when bells chimed for church services, the third, sixth, ninth hours and before Liturgy and Vespers, is still considered by some to receive a special blessing. The churching of women on the 40th day was also considered to be very important, a sure remedy for post-natal depression. The first thing to be placed in a baby’s cradle was the Gospel.

In Lincolnshire there was until recently a custom, or perhaps rather superstition, of receiving confirmation twice – this was thought to cure rheumatism! In the Marches confirmation was said to cure lumbago and sciatica.

In Northumberland, just as among pious Romanian peasants to this day, the funeral clothes of a bride and bridegroom were an integral part of any wedding trousseau.

In the West of England the faithful would put rue, hyssop and wormwood in coffins as symbols of repentance. How far have we come from such piety today!

In spite of 400 years of Protestantism, it is still customary in country areas to eat fish on Fridays, a mere remnant of Orthodox fasting—nevertheless something of which today’s “Neo-Orthodox” seem to be incapable.

As regards blessings, it should not be forgotten that the origin of the expression “Good-bye’ is “God be with you”. Until the Reformation, the expression “Thank you” was less used, being replaced by “God ‘a’ mercy”, (God have mercy), which still survives in the Cockney “Lawks ‘a’ mercy” (Lord have mercy). A popular bedtime prayer was and is

“the White Paternoster”: ‘Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, bless the bed that I lie on”;

I can remember being taught it in childhood.

One local tradition that I cannot fail to mention is that of the old shepherds on the Essex marshes. When they died, they were always buried with some sheep’s wool in their hand. It was said that when at the Last Judgment, they would be asked why they had not attended church on Sundays, they would hold up the wool and thus be forgiven – for they too had been tending their flocks in Christ-loving wise.

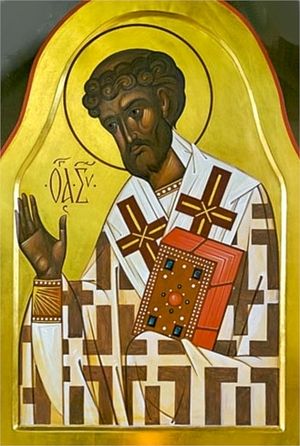

St. Swithin of Winchester

Of all these fragments, reminders of the common Tradition, the most important in my view is that of Christian charity, the practice of the Faith. I have been told countless times by folk of how in our village poor families would systematically cook an extra plate of food for dinner. And this was during the Depression, when all my father had to eat was two crusts of bread and an “oxo mess” a day. Nobody knew who the extra food was for, but invariably a tramp, beggar or unemployed man, fallen on hard times, would come along and then a plate of food would go to him, with the words, “God bless you”. If that is not Orthodoxy, then I don’t know what is.

In these crumbs from the Tradition, fallen like the Canaanite woman’s from the table of the Master, we are reminded that God does not forsake the sincere and the devout, however far from the Church their “leaders” have taken them. Deprived of so many of the riches of the Church, God has remembered them, for

the Spirit bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh and whither it goeth (John 3:8).

In former times England was called “Merry”, not in the corrupt modern sense, but in the ancient sense of the word, “Blessed”. Such customs did indeed bless a land. God does not forsake us, only we forsake God. Old English culture and tradition declared that all Creation is with God and shares in the joy of His Kingdom, for the Earth is here to call us to God. All that exists is a mere reflection of the non-material, real world beyond this one in which we have faith.

That is why, in Old English, the word “Orthodox” was translated by geleafjul – faithful. At a time when we are faced with a choice between turning to the “West”, to Mammon, and turning to the “East”, to Christ, these traditions may help us to make the right choice.

The fragments I have described above, and a great many others, may yet one day be reintegrated into that divine Tradition that we call the Orthodox Christian Faith and Church.

May it be so, ? Lord!

great job…good stuff all.

As a former WASP/new Orthodox convert with family living in the British isles, I really appreciate learning this history! Thank you!

I love all things British, and I just love this! (Also, since my home parish is St. Barnabas, I got a kick out of the fact that in England they refer to our patron as “Barnaby”.) 🙂

Very interesting and illuminating. I was brought up in a low Anglican Church in England and have only recently realised the relics of devotion to the Theotokos that existed, totally unrecognised i.e. “The Lady Chapel”, “Mothering Sunday” – these came clear whne I moved to Wales as the Welsh for them is “Capel Mair” and “Sul y Fam” (Mary’s Chapel – The Mother’s Sunday) – and the Holly and the Ivy which we sang with great gusto alothough no one explained that the Holly was a symbol of the Virgin (they probably didn’t know!). One tiny tiny inaccuracy. “Canterbury” Lamb refers to a district in the South Island of New Zealand famous for exportng lamb to the UK. The eating of lamb may be an old tradition but not the word “Canterbury!!!” I don’t think our Orthodox forefathers got their meat from Down Under!!!

Peter, thanks for the correction!

These are all such beautiful customs. I even remember some from my own childhood, as our home was in a semi-rural area with many very old guys that had farmed since Adam was a boy. None of the locals near me were English, but my relatives of Scottish descent also handed down so much wisdom that helped our annual vegetable garden. These days, we oddly think of these as ‘quaint.’ Children that take violin lessons from me are unaware that food comes from farms, or that cheese can come from sheep, goats or cows. This leads to lots of laughter, Farmers who’ve grown up tilling the ground know harvests are tied to faith, as farming is an act of faith itself. After all, farmers literally “bet the farm” every year on sowing a crop, good rain and good sun at just the right times.

I’ve spent much time in England, and while there made many friends on farms. These customs are a walk down my own memory lane. Our own failure to remember the Creator, especially at planting season, I know for a fact is risky. Growing food is impossible without prayer and blessings. I also bless bread as I bake, and have always done. I wasn’t aware when taught this custom, of its origins. I just knew that it works, just as blessing the oven assures a good meal. This year, I just wonder when it will be warm enough to plant anything outdoors. My seedlings are getting leggy waiting for the snow to melt, and the snows keep on coming down. Does the Jet Stream know something about May 5 this year?