By Robert K. Arakaki

By Robert K. Arakaki

A Journey to Orthodoxy

It was my first week at seminary. Walking down the hallway of the main dorm, I saw an icon of Christ on a student’s door. I thought:

“An icon in an evangelical seminary?! What’s going on here?”

Even more amazing was the fact that Jim’s background was the Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal denomination. When I left Hawaii in 1990 to study at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, I went with the purpose of preparing to become an evangelical seminary professor in a liberal United Church of Christ seminary. The UCC is one of the most liberal denominations, and I wanted to help bring the denomination back to its biblical roots. The last thing I expected was that I would become Orthodox.

Called by an Icon

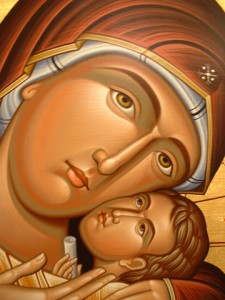

After my first semester, I flew back to Hawaii for the winter break. While there, I was invited to a Bible study at Ss. Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church. At the Bible study I kept looking across the table to the icons that were for sale. My eyes kept going back to this one particular icon of Christ holding the Bible in His hand. For the next several days I could not get that icon out of my mind.

I went back and bought the icon. When I bought it, I wasn’t thinking of becoming Orthodox. I bought it because I thought it was cool, and as a little gesture of rebellion against the heavily Reformed stance at Gordon-Conwell. However, I also felt a spiritual power in the icon that made me more aware of Christ’s presence in my life.

In my third year at seminary, I wrote a paper entitled, “The Icon and Evangelical Spirituality.” In the paper I explored how the visual beauty of icons could enrich evangelical spirituality, which is often quite intellectual and austere. As I did my research, I knew that it was important that I understand the icon from the Orthodox standpoint and not impose a Protestant bias on my subject. Although I remained a Protestant evangelical after I had finished the paper, I now began to comprehend the Orthodox sacramental understanding of reality.

After I graduated from seminary, I went to Berkeley and began doctoral studies in comparative religion. While there, I attended Ss. Kyril and Methodios Bulgarian Orthodox Church, a small parish made up mostly of American converts. It was there that I saw Orthodoxy in action. I was deeply touched by the sight of fathers carrying their babies in their arms to take Holy Communion and fathers holding their children up so they could kiss the icons.

The Biblical Basis for Icons

After several years in Berkeley, I found myself back in Hawaii. Although I was quite interested in Orthodoxy, I also had some major reservations. One was the question: Is there a biblical basis for icons? And doesn’t the Orthodox practice of venerating icons violate the Ten Commandments, which forbid the worship of graven images? The other issue was John Calvin’s opposition to icons. I considered myself to be a Calvinist, and I had a very high regard for Calvin as a theologian and a Bible scholar. I tackled these two problems in the typical fashion of a graduate student: I wrote research papers.

In my research I found that there is indeed a biblical basis for icons. In the Book of Exodus, we find God giving Moses the Ten Commandments, which contain the prohibition against graven images (Exodus 20:4). In that same book, we also find God instructing Moses on the construction of the Tabernacle, including placing the golden cherubim over the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:17–22). Furthermore, we find God instructing Moses to make images of the cherubim on the outer curtains of the Tabernacle and on the inner curtain leading into the Holy of Holies (Exodus 26:1, 31–33).

I found similar biblical precedents for icons in Solomon’s Temple. Images of the cherubim were worked into the Holy of Holies, carved on the two doors leading into the Holy of Holies, as well as on the outer walls around Solomon’s Temple (2 Chronicles 3:14; 1 Kings 6:29, 30, 31–35). What we see here stands in sharp contrast to the stark austerity of many Protestant churches today. Where many Protestant churches have four bare walls, the Old Testament place of worship was full of lavish visual details.

Toward the end of the Book of Ezekiel is a long, elaborate description of the new Temple. Like the Tabernacle of Moses and Solomon’s Temple, the new Temple has wall carvings of cherubim (Ezekiel 41:15–26). More specifically, the carvings of the cherubim had either human faces or the faces of lions. The description of human faces on the temple walls bears a striking resemblance to the icons in Orthodox churches today.

Recent archaeological excavations uncovered a first-century Jewish synagogue with pictures of biblical scenes on its walls. This means that when Jesus and His disciples attended the synagogue on the Sabbath, they did not see four bare walls, but visual reminders of biblical truths.

I was also struck by the fact that the concept of the image of God is crucial for theology. It is important to the Creation account and critical in understanding human nature (Genesis 1:27). This concept is also critical for the understanding of salvation. God saves us by the restoration of His image within us (Romans 8:29; 1 Corinthians 15:49). These are just a few mentions of the image of God in the Bible. All this led me to the conclusion that there is indeed a biblical basis for icons!

What About Calvin?

But what about John Calvin? I had the greatest respect for Calvin, who is highly regarded among Protestants for his Bible commentaries and is one of the foundational theologians of the Protestant Reformation. I couldn’t lightly dismiss Calvin’s iconoclasm. I needed good reasons, biblical and theological, for rejecting Calvin’s opposition to icons.

My research yielded several surprises. One was the astonishing discovery that nowhere in his Institutes did Calvin deal with verses that describe the use of images in the Old Testament Tabernacle and the new Temple. This is a very significant omission.

Another significant weakness is Calvin’s understanding of church history. Calvin assumed that for the first five hundred years of Christianity, the churches were devoid of images, and that it was only with the decline of doctrinal purity that images began to appear in churches. However, Calvin ignored Eusebius’s History of the Church, written in the fourth century, which mentions colored portraits of Christ and the Apostles (7:18). This, despite the fact that Calvin knew of and even cited Eusebius in his Institutes!

Another weakness is the fact that Calvin nowhere countered the classic theological defense put forward by John of Damascus: The biblical injunction against images was based on the fact that God the Father cannot be depicted in visual form. However, because God the Son took on human nature in His Incarnation, it is possible to depict the Son in icons.

I was surprised to find that Calvin’s arguments were nowhere as strong as I had thought. Calvin did not take into account all the biblical evidence, he got his church history wrong, and he failed to respond to the classical theological defense. In other words, Calvin’s iconoclasm was flawed on biblical, theological, and historical grounds.

In my journey to Orthodoxy, there were other issues I needed to address, but the issue of the icon was the tip of the iceberg. I focused on the icon because I thought that it was the most vulnerable point of Orthodoxy. To my surprise, it was much stronger than I had ever anticipated. My questions about icons were like the Titanic hitting the iceberg. What looked like a tiny piece of ice was much bigger under the surface and quite capable of sinking the big ship. In time my Protestant theology fell apart and I became convinced that the Orthodox Church was right when it claimed to have the fullness of the Faith.

I was received into the Orthodox Church on the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1999. On this Sunday the Orthodox Church celebrates the restoration of the icons and the defeat of the iconoclasts at the Seventh Ecumenical Council in AD 787. On this day, the faithful proclaim,

“This is the faith that has established the universe.”

It certainly established the faith of this Calvinist, as the result of the powerful witness of one small icon!

As a student of the theology of icons I believe the voice of Christ speaks to us through His icon. I’m glad you responded to his voice. Welcome home.

Very well written, and very inspiring! I’d be curious to hear what your current thoughts are on Calvin – as a Catholic (Anglican), I’ve always understood Calvin to be the most objectionable of heretics. Are you coming to a similar view, or just less impressed with him than you were before?

A former fundamentalist Baptist, I could NEVER reconcile Calvinism with what I saw to be true about the human condition and my own struggles. A more damaging heresy I had not experienced. With that in mind, I am always so thrilled to join those former Calvinists in the Holy Orthodox Church.

As much as I read and studied and thought about Orthodoxy, it was the truth of icons, particularly St. Patrick, that helped draw me into the Church.

Fr. Ryan,

Thank you! You can find my current view of Calvin in my article: “Calvin vs. the Icon.” You can find it on my blog: OrthodoxBridge.com. But to answer your question, I’ve found Calvin to be a less formidable theologian than I had thought him to be. I wouldn’t characterize my feelings towards him as hostile. It’s more one of respect and appreciation for a former teacher I now disagree with.

Robert

To whomever can give some insight:

What does the author mean when he says,”…the Orthodox sacramental understanding of reality?” I am a Protestant and I do not know if there is a Protestant “view of reality” that could be compared to that of Orthodox view. Can someone educate me?? Thank you.

Elizabeth, there isn’t room to explain here. May I offer a suggestion? Get a copy of “Light from the Christian East” by James R. Payton. It is an excellent treatment of Orthodoxy by a protestant and one of the very best books on Orthodoxy in print.

Elizabeth,

Good question! Many Protestants view matter as spiritually neutral, neither good nor bad, neither holy or defiling. Many Protestants would see icons as a good teaching tool that one looks at, draws certain theological lessons. However, for a Protestant an icon doesn’t reveal the other side of reality. For the Orthodox, on the other hand, an icon is a window to heaven. This Orthodox sacramental understanding of icons is much like the Protestant understanding that God speaks to us through Scripture. I recommend you read the first chapter of Alexander Schmemann’s book “For the Life of the World.”

A great story. I love that you were received on the Sunday of Orthodoxy. How fitting!

Canon 36 of the Council of Elvira states, “Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration.”

Eusebius wrote that even the incarnate Christ cannot appear in an image, for

“the flesh which He put on for our sake … was mingled with the glory of His divinity so that the mortal part was swallowed up by Life. . . . This was the splendor that Christ revealed in the transfiguration and which cannot be captured in human art. To depict purely the human form of Christ before its transformation, on the other hand, is to break the commandment of God and to fall into pagan error.”

Epiphanius (inter 310–320 – 403), considered a “saint” in the Eastern Orthodox church. He was Bishop of Salamis, in Cyprus. He wrote, in the last section of Letter 51 (c. 394), to John, Bishop of Jerusalem:

“I went in to pray, and found there a curtain hanging on the doors of the said church, dyed and embroidered. It bore an image either of Christ or of one of the saints; I do not rightly remember whose the image was. Seeing this, and being loath that an image of a man should be hung up in Christ’s church contrary to the teaching of the Scriptures, I tore it asunder and advised the custodians of the place to use it as a winding sheet for some poor person.”

He goes on to tell John that such images are “contrary to our religion” and to instruct the presbyter of the church that such images are “an occasion of offense.”

It is one thing to offer an opinion before the Church speaks definitively with clarity about a topic, and if your references are accurate this is clearly such a case, but quite another to speak against the Church’s officially proclaimed teaching supported by an entire Ecumenical Council (this one accepted by both East and West to this day). We do not curse these men as heretics, only state that if they held an erroneous position before the Church finally defined a teaching, that they were not infallible. What a shock!

Also the Council of Elvira’s statement was quite a bit more vague than you present. Here’s an article that includes it: The Icon FAQ

The entire Church spoke with clarity at the 7th Ecumenical Council with great specificity about this, and the necessity of iconography to prevent not only idolatry, but a gnostic understanding of the Incarnation. This was supported by the writings of St. John of Damascus, and St. Theodore the Studite.

It is considered so essential to the Christian Gospel that the Church has even declared annual feasts in honor of the 7th Council and the proper return and understanding of iconography, but also has appointed the first Sunday of Lent as the celebration of this important fact – the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy. (Note: not the triumph of iconodules, the triumph of True Christianity).

Here is an article which may be a little enlightening on this matter: The Necessity of Iconography and the Idolatry of Gnosticism

I think your comment on Calvin is a bit lacking here:

“In other words, Calvin’s iconoclasm was flawed on biblical, theological, and historical grounds.”

It’s no surprise that it’s lacking, because the article is specifically about icons. But I would propose that much much more than just Calvin’s ideas on icons was flawed. The whole system he and the other reformers taught were based on secular ideas, and are flawed biblically, historically, and theologically all the way through.